My Memories of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor

The Bencher—May/June 2024

By Mick Lerner, Esquire

America lost one of its treasures when retired Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor passed away on December 1, 2023, at the age of 93. Each time I had the extraordinary privilege of speaking with her, I was in the presence of one of the greatest Supreme Court justices in history, not simply because of her selection as the first female justice but also because of her performance on the court.

America lost one of its treasures when retired Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor passed away on December 1, 2023, at the age of 93. Each time I had the extraordinary privilege of speaking with her, I was in the presence of one of the greatest Supreme Court justices in history, not simply because of her selection as the first female justice but also because of her performance on the court.

She has been called “The Most Consequential Justice,” who sided with the majority in many five-to-four decisions during her almost 25 years on the bench, such that some court commentators called it “The O’Connor Court.”

The historic significance of her appointment to the court is well-recognized and well-recorded, including how she became a justice, then adeptly and brilliantly fulfilled her role, paving the way for other female justices. Her ability to develop friendships with other justices and build coalitions by navigating among their disagreements helped resolve some of the most significant issues during her time on the court.

The analyses and wording in the majority opinions she authored are not the only part of her great legacy. As a role model for a generation of young women, she inspired them to believe they, too, could break the glass ceiling in the legal profession, in the judiciary, and elsewhere. And she was a champion for civics education in schools and for ethics and civility in public discourse.

Based upon the few meetings I had with Justice O’Connor, I want to emphasize some of her outstanding aspects:

First was her unwavering enthusiasm for women to become lawyers and judges and her constant proselytizing, whenever speaking to women in any group, encouraging them to seek positions in the judiciary.

The second, in her later life, was creation of the iCivics internet educational program and her often-stated conviction that there is an absolute need for civics education for K–12 students.

Third was her constant, enthusiastic, and articulate support of the American Inns of Court and its movement—support that took the form of attendance at numerous American Inns of Court events and many speeches promoting the mission and accomplishments of Inns around the country.

Her second biography, The Majesty of the Law, consists of reflections as a justice, with in-depth, well-thought-out reflections about her nomination to the court, her interaction with other justices, her view of the court’s procedures, and her appraisal of the weighty issues that came before her on the court and how she dealt with them.

In the book, she also discussed her views of the role of lawyers and the reasons she supported the American Inns of Court so fervently.

I first met Justice O’Connor at the 2001 American Inns of Court Celebration of Excellence. Knowing of her relationship with Stanford University, having received undergraduate and law school degrees there, I mentioned that I had attended the annual Stanford Reunion on the campus in Palo Alto the week before. Both she and her husband were excited to hear about the reunion. It was then that I learned how supportive she had become of the American Inns of Court, on which board I was serving as a trustee.

I first met Justice O’Connor at the 2001 American Inns of Court Celebration of Excellence. Knowing of her relationship with Stanford University, having received undergraduate and law school degrees there, I mentioned that I had attended the annual Stanford Reunion on the campus in Palo Alto the week before. Both she and her husband were excited to hear about the reunion. It was then that I learned how supportive she had become of the American Inns of Court, on which board I was serving as a trustee.

My next opportunity to talk with Justice O’Connor was in May 2005, when she came to Kansas City to receive the Harry S. Truman Good Neighbor Award. Noting she had a copy of his “The Buck Stops Here” sign on her chambers desk, she explained that, as a Supreme Court justice, she too could not pass the buck to others and had to make difficult decisions, just as Truman did during his presidency.

At the private dinner the night before the award luncheon, she recounted how, when interviewing for employment in a prestigious law firm after graduating third in her Stanford Law School class, she was asked how fast she could type, indicating she would be considered to become a secretary there. That story conveyed how much discrimination women faced in the 1950s and how extraordinary it had been for her to ultimately be nominated to the Supreme Court of the United States.

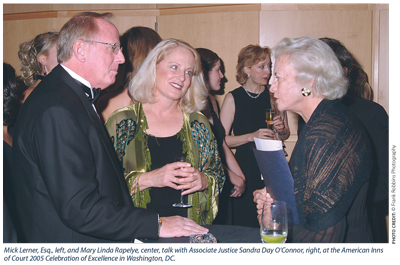

At the 2005 Celebration of Excellence, I watched as groups of young women approached Justice O’Connor, who asked what each planned to do with their legal training, then encouraged them to consider pursuing a judicial position.

The last time our paths crossed was at the 2013 American Inns of Court Professionalism Symposium, long after she had retired from the court. Greeting her when she walked into the conference room on the arm of her friend Justice Randy J. Holland, my heart sank seeing her followed by two U.S. marshals caring an oxygen tank and a defibrillator. My fears about her health were alleviated when she stood, straight and seemingly comfortably, at the lectern, delivering to a large audience a 20-minute extemporaneous speech using no notes at all. With self-deprecating humor and humility, she described herself as simply “a retired old cowgirl” who did not deserve all the attention she was receiving.

Her topic, the iCivics program she established, explained in detail how this internet game and program captured the interest of middle school students across the country, educating them in the principles of their government. Expressing concern about a lack of civics education in middle schools and high schools, she emphasized, “The practice of democracy is not passed down through the gene pool. It must be taught and learned by each generation.”

To this day, Justice O’Connor lives on in a video she recorded extolling the virtues and importance of the American Inns of Court mission. It is fitting that this issue of The Bencher honors Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, whom I will always remember as her majesty in the law.

Mick Lerner, Esquire, is an attorney practicing in Overland Park, Kansas. He is the past president of the Earl E. O’Connor American Inn of Court and a former member of the American Inns of Court Board of Trustees.