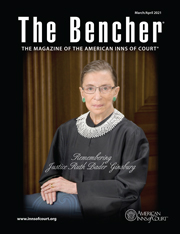

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: A Legal Icon While a Model of Civility

The Bencher—March/April 2021

By Vanessa Day, Esquire

“I got the idea that being a lawyer is a pretty good thing because in addition to practicing a profession, you could do some good for your society, make things a little better for other people.”

—Ruth Bader Ginsburg, 2015

I am inspired by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the late associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, because she cared about people and wanted justice for all. She modeled civility during her distinguished legal career and demonstrated her appreciation for the diversity of thought. She did much good for our society through her opinions and dissents.

Model of Civility

Throughout her career, Ginsburg showed that you can disagree without being disagreeable. The book “The RBG Way: The Secrets of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Success” mentions “when she dissents, she doesn’t speak angrily, but instead acknowledges her opponent’s side before discussing her opinion.” Ginsburg also did not want the public to lose faith in the judiciary system or process by insulting her colleagues. “Ginsburg has said that the most effective dissent, in her mind, is one that can survive purely on its own legal basis,” the book stated.

Ginsburg liked to teach. A lesson gleaned from her philosophy is “belittling your opponent does nothing to further your argument and will likely make them less interested in listening anyway.” She believed in using persuasion instead of anger to bring people to her way of thinking.

Opinions and Dissents—Fighting for What Is Right

Ginsburg’s majority opinions made society better by protecting the rights of people with disabilities and those with lower socioeconomic incomes. In the case

Olmstead v. L.C. (1999), the Supreme Court ruled under Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act that states are required to provide community-based treatment for persons with mental disabilities when the state’s treatment professionals determine that such placement is appropriate, the affected persons do not oppose such treatment, and the placement can be reasonably accommodated, taking into account the resources available to the state and the needs of others with mental disabilities. In

M.L.B v. S.L.I. (1996), the court ruled that a parent can’t be denied the right to appeal a parental termination case because of the inability to afford the filing fee.

Ginsberg did not compromise her values just to be in the majority. In 2009, when speaking at the Harvard Club in Washington, DC, she said, “Although I appreciate the value of unanimous opinions, I will continue to speak in dissent when important matters are at stake.” She chose her battles, and she did not dissent every time she disagreed. Instead, she was strategic in her use of dissents to advance the law and important principles. She used dissents to speak to other branches of government and to the public to spark immediate change. She also used dissents to obtain future changes in the law. On February 6, 2015, while speaking at the Tanner Lecture on Human Values, she said, “I think most of my dissents will be law someday.”

Ginsburg was also a champion of women’s rights and equality. Her dissent in the

Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. Inc. (2007) led to changes in the law regarding pay discrimination against women. In 2009, President Obama signed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act.

Ginsburg knew the importance and value of voting in a free democracy. Her dissent in

Shelby County v. Holder (2013) recognized that the preclearance requirements of the 1965 Voting Rights Act are still needed to protect against discrimination. She wrote in her dissenting opinion, “Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

Appreciation of Diversity of Thought

Ginsburg’s friendship with Justice Antonin Scalia was an example of how much she appreciated diversity of thought. While the two did not have the same judicial philosophy, they were friends and respected colleagues. As mentioned in “The RBG Way,” “Ginsburg once explained that the difference came from the way they interpreted legal texts but that they had a shared reverence for the Constitution and the U.S. judiciary they served. Collegiality on the court is necessary for the justices to do the challenging job assigned to them. It is reported that the two exchanged their opinions with each other in

United States v. Virginia (1996) so each could strengthen their arguments before circulating their opinions to others on the court.

Ginsburg listened and respected opinions of others. Although she recognized that better solutions are found with diversity of thought, she did not compromise her position when she believed she was right on an issue. Scalia and Ginsburg disagreed professionally on legal issues; they did not make their disagreements personal. “The RBG Way” cites Scalia’s son as saying the two justices’ differences actually bolstered their friendship.

On a personal level, they looked for commonalities such as their love of the law and the opera, and they even went on vacation together.

Another example of her appreciation of diversity of thought was noted in a commemorative edition of Time magazine: “Ginsberg befriended Justice Sandra O’Connor, but their visions of jurisprudence were very different.” It stated that the difference in their views was illustrated in the

Harris v. Forklift (1993) employment discrimination case. O’Connor used a “severe and pervasive standard” regarding the conduct a woman must withstand, while Ginsburg’s standard was based on equality: Did the conduct make it harder for the woman to do her job than a man in the same job?

During her confirmation hearings in 1993, Ginsburg said, “I would like to be thought of as someone who cares about people and does the best she can with the talent she has to make a contribution to a better world.” I believe she achieved her goal.

Vanessa Day, Esquire, is an attorney in the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Office of the Assistant Commissioner in Trenton, New Jersey. She is a member of the Justice Stewart G. Pollock Environmental American Inn of Court.