Blockchain: Beyond Cryptocurrency

The Bencher—November/December 2018

By Graham K. Bryant, Esquire

Bitcoin became a household name over the past year as front-page news reports tracked its meteoric rise and analysts speculated whether the “bitcoin bubble” was about to burst. The recent roller-coaster ride in bitcoin value, peaking at an all-time high of just under $20,000 per bitcoin, demonstrates that digital currencies have real-world value. Unsurprisingly, the financial and legal sectors are paying close attention.

Bitcoin became a household name over the past year as front-page news reports tracked its meteoric rise and analysts speculated whether the “bitcoin bubble” was about to burst. The recent roller-coaster ride in bitcoin value, peaking at an all-time high of just under $20,000 per bitcoin, demonstrates that digital currencies have real-world value. Unsurprisingly, the financial and legal sectors are paying close attention.

The advent of bitcoin and the blockchain technology that powers it heralds a new period of disruption for the legal profession. Lawyers will need to become familiar with these technologies—and their ethical implications—to remain competitive as the practice of law continues to evolve.

Cryptocurrencies Become Mainstream

Despite being the most familiar name, bitcoin is just one of many “cryptocurrencies.” A cryptocurrency is a currency that exists only digitally, uses a decentralized system to record transactions and manage the issuance of new units, and relies on cryptography to prevent counterfeiting and fraudulent transactions.

Cryptocurrency is serious business. The top five cryptocurrencies have a combined market capitalization of over $200 billion. The explosion in cryptocurrencies is largely due to the unique value they have compared to any other medium of exchange: They are decentralized.

Some form of intermediary is involved in nearly every transaction. A bank or credit card company is usually involved in even the simplest purchases, while more elaborate transactions involve escrow agents and lawyers, all with their accompanying fees and delays. These transaction costs are major considerations when planning any significant transaction.

Unlike every other medium of exchange, cryptocurrencies operate free from central authorities such as banks or payment processors. Without middlemen, cryptocurrency users can buy and sell directly to one another in a peer-to-peer fashion without incurring the costs inherent in any centralized market. In fact, the only transaction cost associated with cryptocurrency use is the conversion fee for exchanging cryptocurrency for U.S. dollars or another traditional currency.

Potential Ethical Consequences

The benefits of cryptocurrencies over other currencies means that consumers want to use them to purchase goods and services. Unsurprisingly, many lawyers are under pressure from their clients to accept cryptocurrencies as payment for legal services, and some are already doing so.

To date, Nebraska is the only state that has issued a legal ethics opinion (No. 17-03) specifically addressing a lawyer’s duties when receiving cryptocurrency as payment for legal services. Attorney Matt McKeever, with the firm of Copple, Rockey, McKeever, and Schlecht, asked Nebraska’s Lawyer’s Advisory Committee to consider the issue given the rapid rise of financial technology companies that have transformed the region into a hub for nontraditional payment processing. Other states facing similar concerns are relying on the Nebraska opinion as a lone lighthouse in otherwise uncharted waters. https://supremecourt.nebraska.gov/sites/default/files/ethics-opinions/Lawyer/17-03.pdf

The September 11, 2017, opinion states that Nebraska lawyers may accept cryptocurrency payments, but it includes a major caveat: They can do so only if they immediately convert the payment into U.S. dollars. Any refunds relating to the transaction must also be made in U.S. dollars.

The opinion’s immediate-conversion requirement is rooted in the traditional rules that lawyers cannot access client funds until earned and that fees earned must be reasonable. Lawyers may accept money or property in exchange for their services, but any property accepted as payment must have a valuation; otherwise, it would be impossible to determine whether the fee is reasonable. Likewise, lawyers have to treat money and property differently; client funds belong in trust accounts, while client property must be kept safe through other methods.

It’s easy to be ethical by depositing a retainer in the trust account or securing a client’s diamond ring in a safe. But cryptocurrencies complicate application of these well-known principles because they rest in the gray area between money and property. A lawyer cannot deposit cryptocurrency directly into a trust account so it appears that cryptocurrency payments are not like client funds. In that case, they must be client property subject to the duty to safeguard. But how can a lawyer safeguard a cryptocurrency retainer from the inevitable volatility endemic to cryptocurrency values?

By requiring immediate conversion of cryptocurrencies, the Nebraska opinion dodges this thorny issue of whether cryptocurrencies are money or property. Forcing lawyers to convert cryptocurrencies into U.S. dollars immediately ensures that cryptocurrency payments have a value for purposes of applying these ethics rules.

Although the rule seems neat, it leaves open the question of who must bear the transaction fees for the mandatory conversions. As noted earlier, the only transaction cost for using cryptocurrencies is that of converting them into a traditional currency. That cost can be substantial. The opinion provides no guidance about who must pay this fee. That leaves lawyers and clients to bargain to determine which party must bear the risk of decreased value (or reap the windfall of a rise in value), an added complication that undermines the convenience factor that makes cryptocurrencies attractive in the first place.

There may be another more mundane reason for the Nebraska opinion’s immediate-conversion requirement. As Jim McCauley, ethics counsel for the Virginia State Bar, observed in the June 2018 issue of Virginia Lawyer magazine, “No regulatory bar is currently equipped to audit bitcoin transactions and storage.” http://www.vsb.org/docs/valawyermagazine/vl0618_cryptocurrency.pdf. Current approaches to regulating lawyer bookkeeping simply have not kept pace with technology; conducting audits of trust accounts that include cryptocurrency assets would be nearly impossible. By requiring lawyers to assume the risk of converting cryptocurrency payments into U.S. dollars, the Nebraska opinion left that issue for another state’s ethics committee to resolve.

Lawyer acceptance of cryptocurrency payment is a rapidly developing topic, and attorneys who are considering the practice—or who already accept cryptocurrency payment for legal services—should monitor this area closely for further developments.

Blockchain and Distributed Ledger Technology

The technology that makes cryptocurrencies possible and allows for a decentralized market is called “blockchain.” Think of blockchain as, fundamentally, a digital transaction ledger. Blockchain technology is the latest stage in the evolution of the paper transaction register every old-time general store used to track sales.

The technology that makes cryptocurrencies possible and allows for a decentralized market is called “blockchain.” Think of blockchain as, fundamentally, a digital transaction ledger. Blockchain technology is the latest stage in the evolution of the paper transaction register every old-time general store used to track sales.

Importantly, blockchain applications are not limited to facilitating currency transactions. Consider that the deed books in your local courthouse’s records room are, in essence, paper registers that verify and record transactions. In the same sense, blockchains provide a platform for a variety of applications requiring accurate, indelible records of transactions. Let’s examine how blockchain technology works.

A blockchain is a decentralized, purely digital ledger that encrypts every transaction and distributes it throughout a network. For this reason, blockchain is also called distributed ledger technology. The distribution of transactions across a network is what makes blockchain technology decentralized. Rather than a single computer that hosts the blockchain, there are multiple identical copies of the whole blockchain across the network.

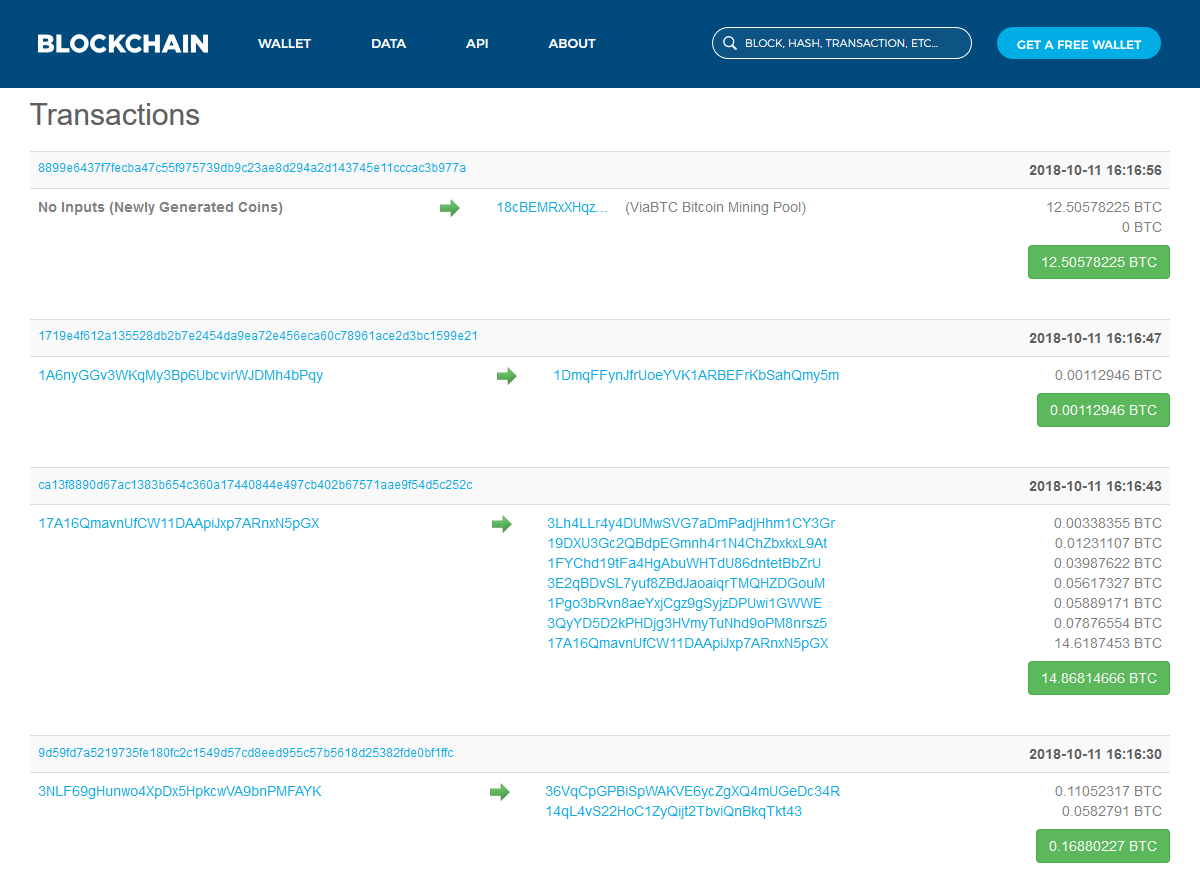

Because each transaction recorded on the blockchain is encrypted, the blockchain takes the form of a public record that is nearly impossible to hack or alter. The blockchain keeps a complete record of every transaction from its inception forward, validated and confirmed by cryptographic calculations performed by the distributed computers. To clarify what a series of blockchain transactions might look like, refer the image below, which depicts a selection of transactions from October 11, 2018, recorded on Block #545340 of the bitcoin blockchain.

The transactions are publicly visible but encrypted—all a viewer can see are the addresses between which certain amounts of cryptocurrency are exchanged. Because every computer on the bitcoin blockchain preserves the whole blockchain, these transactions cannot be altered.

The result of this process is a reliable digital system that permits transactions to occur securely and without a need for third-party facilitation. Blockchain thus allows for automatic, decentralized proof of trust. The participants in a blockchain transaction do not necessarily know one another, but because of the secure and reliable nature of blockchain technology, they can exchange value with certainty despite the lack of a central validating authority.

Applications and Implications for Lawyers

The essential attraction of blockchain technology is that it allows for trusted, secure transactions without recourse to a central authority such as a bank. With that in mind, it may come as a surprise to learn that financial institutions are leading the charge in blockchain technological development.

It makes sense for big banks to take a keen interest in blockchain’s disruptive potential. After all, if banks make much of their profits from transaction costs, then they stand to lose out if decentralized transactions become the norm. Likewise, the legal field will not be immune from blockchain-driven changes. Lawyers must take notice of blockchain or risk being left behind.

Potential legal applications for blockchain technology are already becoming apparent, including some that will affect even the smallest law practices:

Smart Contracts: Smart contracts are perhaps the most commonly cited legal application for blockchain. Just as blockchains can store cryptocurrencies, the same distributed ledger infrastructure can also store executable computer code. Using “if this, then that” logic, entire contracts can be coded into an immutable, self-executing blockchain. This ability has major implications for transactional lawyers.

For instance, a complex logistics contract could be coded into a blockchain along with contingent triggers. One term might provide that if delivery occurs before a certain date, then the seller receives a monetary bonus. Internet-of-things tracking devices would automatically detect arrival of the shipping container at the port, triggering the relevant smart-contract provision. With this technology, deliveries could be tracked and payments sent without the need for manual verification. In ordinary logistics contracts, provisions governing these processes are frequently litigated, and even if all goes as planned, payouts can take months to process. Smart-contract applications could dramatically streamline the logistics industry, and major companies, such as Maersk, are already investing heavily in the technology.

What if there’s noncompliance with the contract? The same “if this, then that” logic coded into the blockchain smart contract would apply. For instance, if delivery occurs after a certain date, then the shipment is rejected. If the particular exigency is not contemplated by the smart contract, ordinary principles of contract law would apply with the smart contract being construed against the drafter—the party who coded the agreement terms into the blockchain.

Logistics contracts are just one illustration of smart-contract potential. Even ordinary insurance contracts could become more efficient using the blockchain smart-contract model.

Corporate Filings: Because blockchain provides an unalterable record of transactions, it naturally lends itself to record management. Delaware launched the Delaware Blockchain Initiative in May 2016 seeking to leverage blockchain technology to overhaul the laborious, paper-based filing system in the Delaware Division of Corporations. The blockchain technology promises to automate record retention, release, and renewal, as well as streamline UCC record searches. When fully implemented, the system should reduce errors and operational costs when compared to a manual filing process.

Land Records: For many of the same reasons, blockchains could be the deed books of the future. Unlike land records stored in massive volumes in a dedicated courthouse room, land records recorded on a blockchain ledger would be easily searchable and immutable. All transactions are recorded on a blockchain for all time, meaning land record blockchains have the potential to eliminate broken chains of title caused by sloppy recordkeeping and to permit instant recording. Further, because of the distributed nature of blockchain technology, banks, real estate offices, insurance companies, and property lawyers could all have access to the entire chain from their own computer—no need for a trip to the courthouse.

Notarization: Blockchain is at its core a technology designed to provide trust. Just as signet rings, wax seals, or diplomatic apostilles are designed to authenticate documents and prevent fraud, blockchain has the ability to serve as an authentication technology that could ultimately replace inefficient notarization. Several startups employ blockchain technology to offer online notary services, and some of these are already being integrated into mainstream office software. This vote of confidence suggests the market for blockchain-based notarization services is on the rise.

These examples illustrate just how versatile distributed ledger blockchain technology is. Given the myriad applications for blockchain in the legal world, now is the time for lawyers to become familiar with the technology. A lawyer does not have to be a programmer or computer scientist to be effective using blockchain, but he or she does need to cultivate a general understanding of blockchain and its related technologies to be prepared for life in tomorrow’s law office.

Graham K. Bryant, Esquire, is a law clerk to Justice William C. Mims of the Supreme Court of Virginia. He focuses on developing trends in appellate law and legal writing. He is an active member of the John Marshall American Inn of Court in Richmond, Virginia. He also serves on the Virginia State Bar’s Special Committee on the Future of Law Practice, studying emerging trends and technologies—such as blockchain—that may revolutionize the practice of law.