Meg S. Glasmann

2024 Pegasus Scholar Report

Being a Pegasus Scholar has been one of the most rewarding experiences of my life. Six weeks abroad spent immersed in international law and culture has forever changed my legal career. Similar to my last time abroad in 2013 to compete in the javelin event in at the Keihaskarnevaalit in Pihtiputas, Finland, and at the Pan American Junior (U20) Championships in Medellin, Colombia, I knew I had big shoes to fill as an American Inns of Court Pegasus Scholar, having some 68 exceptional scholars come before me.

I decided to visit a local art store before my trip to pick up a sketch book and set of watercolors to help document the experience, and I set forth on my whirlwind adventure.

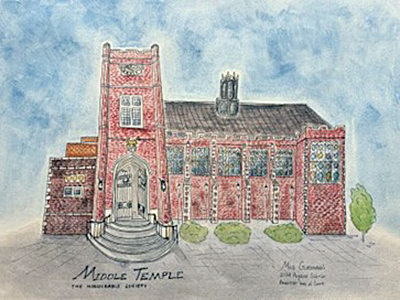

A Watercolor to Commemorate the Trip

I decided, at Cindy Dennis’ recommendation, to paint Middle Temple. I am proud of the result and I hope to paint the other four Inns as a way to commemorate my Pegasus Scholar experience. If you are interested in purchasing a print of this painting, please reach out to megan.glasmann@gmail.com.

One of the themes of my trip was iconography. Perhaps because my own state flag recently underwent big changes in Utah, I was primed on this trip to look for symbols, and wonder what they meant. I was startled to find them everywhere in Europe.

In my report, you’ll find my curiosity scattered throughout, as well as photos and sketches of my time abroad.

Off to the Races!

The first day in London, we met up our Temple Bar Scholar counterparts, Michaeljit Sandhu, Elise Baranouski, Julia Fine, and Hannah Templin. Our group of six scholars met with the AIC President, Judge Consuelo Callahan of the Ninth Circuit, U.S. Court of Appeals; and AIC Executive Director, General Malinda Dunn. Following our initial meeting, we enjoyed a lovely dinner at a local pub with members of the AIC amity visit cohort, which included legal practitioners from across the United States.

Legal London

In the 1320s, London threw all the lawyers out of the city. This is why the Royal Courts of Justice and the Inns of Court are all technically just outside of the city limits of London.

While I learned that there are generally no flags flown in the U.K. courts (unlike the U.S.), most if not all have the royal crest hanging on the wall. The royal crest consists of several inscriptions, a lion, and a unicorn. Rather surprisingly, the words on the crest are not English or Latin, but instead French.

Curious as to why the English royal crest contains French mottos, I read up on the history.

The first inscription originated with Richard I the Lionheart, who in 1198 at the battle of Gisors proclaimed “God in my right” to assert his claim to France. Hence, the French “dieu et mon droit.”

The origin of the second saying is less clear. “Honi soit qui mal y pense” means “Shame on anyone who thinks evil of it.” This is the motto of England’s most noble order of chivalry, the Order of the Garter, which was founded by King Edward III in the mid 14th century.

Opening of the Legal Year at Westminster Abbey

One of the highlights of the Pegasus scholarship exchange was attending the Opening of the Legal Year at Westminster Abbey. Steeped in tradition, this unique ceremony honors the legal profession with a profound gathering of members of the judiciary, speeches, and music to mark the beginning of a new legal year in the United Kingdom.

One of the highlights of the Pegasus scholarship exchange was attending the Opening of the Legal Year at Westminster Abbey. Steeped in tradition, this unique ceremony honors the legal profession with a profound gathering of members of the judiciary, speeches, and music to mark the beginning of a new legal year in the United Kingdom.

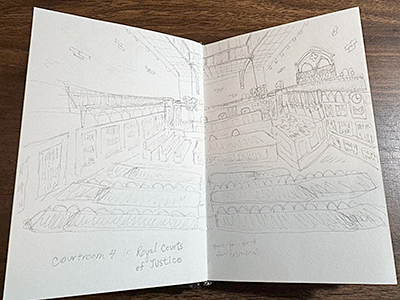

The Royal Courts of Justice

During our scholarship exchange, we enjoyed a walking tour of the Royal Courts of Justice (RCJ). Constructed in the years 1882-87, the RCJ was built to mimic a cathedral: as if you could feel the sheer power of English law upon your shoulders. Known for its splendor and gravitas, the RCJ was used as one point for the London Fashion Week. Also, apparently the main hall of the RCJ used to have an English pub in it!

During our scholarship exchange, we enjoyed a walking tour of the Royal Courts of Justice (RCJ). Constructed in the years 1882-87, the RCJ was built to mimic a cathedral: as if you could feel the sheer power of English law upon your shoulders. Known for its splendor and gravitas, the RCJ was used as one point for the London Fashion Week. Also, apparently the main hall of the RCJ used to have an English pub in it!

While at the RCJ, we met with the Lady Chief Justice. We learned that while she was taking her oath of office, they switched out all of the plaques in the RCJ from Lord to Lady, as she is the first ever Lady Chief Justice!

We also met with the Master of the Rolls. There have only been 98 Masters of the Rolls since 1286. It was not until the 1600s, however, that the Master of the Rolls was a judge. These distinguished members of the English courts are responsible for looking after all of the records spanning England’s extensive history: England has a discrete record going back 1000 years. Given this astonishing amount of archival data, it is perhaps not surprising that they have hundreds of kilometers of records, some of them stored in abandoned mines.

In the early days, the Master of the Rolls worked for the Chancellery Court (the King’s Court) and the law happened mostly on “the manor” and justice was local. Often, justice was administered by the lords of the manors before the King’s Court could reach them. At the time, you could only appeal your case by asking the King—who could have been anywhere (i.e., on crusade). Writs developed during this period, likely in response to the inaccessibility of direct appeals to the King.

The English Inns of Court

During our time in London, we had the opportunity to visit all four Inns of Court in London. Inn refers to a large household, and given the longstanding history of the Inns being both educational and residential centers for the law, it makes sense that the legal epicenters of London are called Inns. Each Inn has a hall, a chapel, and a residential area.

Grays Inn, Middle Temple, Inner Temple, and Lincoln’s Inn each date back to medieval times and are the epicenters of Legal London. Each Inn has its unique coat of arms, and within each Inn there are hundreds of smaller coats of arms on panels hanging in hallways and in stained glass windows commemorating various members of the Inns over their long histories.

During medieval times, there were as many as 14 inns of court. In 1903, Sergeant’s Inn folded, leaving only four Inns in existence.

Lincoln’s Inn of Court

The reason for why Lincoln’s Inn is called Lincoln’s is a bit of a mystery. While the general assumption is that the name stems from the Earls of Lincoln, their property was far from the grounds of Lincoln’s Inn, so this is likely mistaken. Despite this, the lion on the Lincoln’s Inn crest is the same as the one from the Earls of Lincoln, so it is possible that there were lawyers from Earls that moved to the present area of the Inn.

Lincoln’s records go back to 1422. Despite this, the Inn has grounds to believe that it was a mature institution by 1417. The original building, which was built sometime in the 13th century, has one remaining archway. The original building was made of clay taken from the rabbit warren. The rabbits were introduced by the Romans in the early times, and the students at the Inn were known to shoot the rabbits with bows and arrows! The “new” building was constructed from 1490-1492. It is this building that remains on the grounds today, with some renovations conducting over the years. Charles Dickens was known to frequent Lincoln’s Inn.

Old Hall at Lincoln’s Inn was used at one point as a Court of Chancellery, and later as a Court of Appeal. There is a crypt under Old Hall, and recently they found a portrait of Thomas Moore in it. Thought initially to be a copy, a 16th century specialist from the National Portrait Gallery determined it was a real 16th century portrait; but because of the arid climate of the crypt (too dry and hot), the painting was in pretty rough shape. The painting is currently being restored.

During our visit to Lincoln’s Inn, we had the chance to eat lunch in the Great Hall. While there, I was enamored by the large fresco painting that occupies the space above the high table. I learned that the fresco, which was painted by George Frederick, started causing problems for the Inn almost immediately after its installation, in large part because of the London humidity. In 2019, there was a major cleaning of the fresco. The following year, the roof was restored and a scaffolding pole went through the mural. Oops!

One of the claims to fame at Lincoln’s Inn is the “Golden Book.” Lore has it that during a drunken evening at the Inn, King Charles II was in attendance and asked to sign the ledger that all barristers affiliated with the Inn would sign. King Charles II was the first in the royal family to join the Inn, and his signature graces one of the pages in the Golden Book. Subsequently, other members of the royal family signed the Golden Book, following in the footsteps of King Charles II.

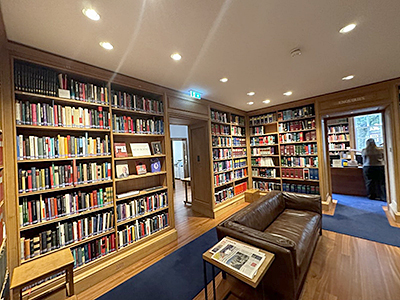

The Golden Book is one of many amazing ancient texts and manuscripts housed at Lincoln’s Inn Library. The Library at Lincoln’s Inn is the oldest in the country, and has existed since the 1400’s. The current library building was constructed in 1845. Ever curious about these incredible archives, I befriended the head librarian, Dunstan Speight, and he was kind enough to show us the Golden Book. I returned on another day to view the Neville Statutes and a number of other stunning texts that Dunstan kindly pulled from the collections for me to view.

Gray’s Inn

Gray’s Inn has been around since the 1300s. It is one of the smallest Inns of Court, but it is certainly one of the most regal.

During a formal banquet at Gray’s Inn, I had the pleasure of witnessing AIC President Judge Callahan be honored as an honorary bencher of Gray’s Inn. I also got to partake in a special Inn’s toast, which according to legend, can be done sitting down based on a grant of permission by Queen Elizabeth I (but at Lincoln’s Inn they attribute the same right to King Charles II).

Middle Temple

In 1573, the Great Hall of Middle Temple was built. Unfortunately, the Great Fire of London impacted a significant portion of the Inn, but the double hammer beam roof is original to the building. During WWII, the wooden façade side of the Great Hall was partially destroyed during the Blitz. The American Bar Association heled sponsor the restoration following the war. The new bits used to repair the hall were taken from a medieval barn that was actually older than Middle Temple.

Despite the extensive damage the Inn during the Blitz, all of the stained glass is original, from the 16th century. It was taken down and hidden during the second world war. Similarly, all of the Inn’s paintings were taken down and stowed during WWII. The wine cellar at Lincoln’s Inn is where the large Charles I painting was kept, rolled up as it as was too big to move the frame!

One of Middle Temple’s claims to fame is that the high table in the Great Hall was made from a single oak tree floated down the river from Windsor forest by the Queen.

The Victorians first used the armory as decoration in the Great Hall. It was previously likely housed in an armory or more practical place, in case they needed to protect the hall.

The original charter for Middle and Inner Temple used to be kept in a metal chest rolled up underneath the alter at Temple Church with it positioned halfway between Middle and Inner Temple. The metal chest could only be opened with a key from both of the Inns! Temple Church is where the magna carta was sealed in 1216.

While at Middle Temple, I met Christa Richmond, Director of Education. We became fast friends, and she later invited me to attend an opera with her at Glyndebourne Opera house!

Inner Temple

In 1698, King James I gave the land underneath Inner Temple to the Inn in perpetuity. The late Queen Elizabeth II reconfirmed this gift in 2008.

In 1698, King James I gave the land underneath Inner Temple to the Inn in perpetuity. The late Queen Elizabeth II reconfirmed this gift in 2008.

In Inner Temple Great Hall, there are four portraits of men known as the fire judges. They have black frames to commemorate the Great Fire of London and their tireless work following the city-wide disaster.

Inner Temple library was one of my favorite places to visit. While there, I had the chance to access medical law related to my ongoing bioethics research in the U.S. I also learned about the marvelous and strange history of the Inner Temple Library. For example, in the 1700s, they blew up the library on purpose to save the rest of the Inn during a fire. And, in the 1940s, all valuable items were vacated to Inn member’s country estates. Unfortunately, all records from the library were destroyed in a 1941 bombing, but thankfully all of the vacated texts and valuable items were saved.

The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom

We had the honor of meeting with the Chief Justice of the U.K. Supreme Court during our first week in London. The Chief Justice, Lord Reed, was very excited to share a case with me: apparently, in ancient Greece, there was a personal injury case involving a javelin!

Lord Reed also shared with us some of the differences between the U.K. and U.S. supreme courts. For example, some 80% of all UKSC cases are unanimous; collaboration and unity are high priorities for Lord Reed.

Another difference between the U.S. and U.K systems is in nomenclature; whereas in the U.S., we call the folks who work for judges and justices “law clerks,” in the U.K., they call them “judicial assistants.” They use a different phrase for writ of certiorari, too: in the U.K., it’s known as a petition to appeal (PTA).

Interestingly enough, the UKSC has only existed for the past 15 years. Before that, the upper parliamentary body (the House of Lords) was responsible for PTAs.

When the UKSC was established, the Court was very intentional in the development of its iconography. The UKSC emblem unifies each of the four domains of the United Kingdom: the Tudor rose of England; the leek of Wales; the thistle of Scotland; and the flax of Northern Ireland. Each of these symbols make up a continuous circle inside of an omega.

In my last week in London, I returned to the UKSC to observe several hearings and learn from the justices and their JAs. This was truly a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, and it was such a treat to observe the different style of oral advocacy employed by various barristers before the Court. Additionally, I had the distinct pleasure of shadowing Lord David Richards of Camberwell during my visit. Lord Richards and I talked extensively about the distinctions between the U.S. and U.K. legal systems. We also talked about our shared love of the outdoors. I told him he must make a trip to Utah!

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

In addition to sitting on the UKSC, all justices also sit on the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (“the Privy Council”). The Privy Council fills a very unique niche, acting as a supreme court for former British colonies, such as Trinidad & Tobago, the Cayman Islands, and the Bahamas. Many Bahamas cases are commercial in nature, due to trade routes passing through the area from Hong Kong, China, and Japan. The Privy Council is working diligently to expand its bench to be more inclusive of the regions it oversees. Recently, the first Caribbean judge was appointed to the Privy Counsel.

Legal Canons

I was very curious to learn about how the UKSC deals with legislative and constitutional interpretation. I learned that the predominant theory is known as “purpose of approach,” which is similar to, but ultimately still quite different from, textualism. But while the UKSC might use something adjacent to textualism when interpreting legislation and constitutions, the UKSC is expressly not an originalist court. The UKSC applies a living constitution approach instead.

When overturning law, the Court must consider how the change will impact contracts and burden the public, and consider whether society has changed since the precedent was written. The Court must also contemplate whether the precedent was erroneous when it was written.

Parliament

One of my favorite parts of the trip was visiting Parliament. We toured the Palace of Westminster, which was begun by Edward the Confessor in 1044. While there, we had the chance to view and learn about both the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

Unfortunately, as with many buildings in Legal London, Parliament burned during the Great Fire of London. It was rebuilt in a neo-gothic style.

The Old Bailey (the Central Criminal Court of England and Wales)

We had the chance to sit in on part of an attempted murder trial at the Old Bailey. Seeing a room full of barristers in full wigs and robes attire was something else!

Barristers’ Chambers

While in England, I had the chance to visit and learn from three distinct barristers’ chambers.

33 Bedford Row Chambers

I met Jamil Mohammed and Constance Whippman at 33 Bedford Row Chambers. Jamil gave us a tour of the chambers, explaining the “pigeonhole” system used for paper briefs, similar to a court dropbox or mailroom. Jamil also explained the “cab rank” rule that barristers follow, which requires barristers to take on all cases they are given unless you lack competency. I had the chance to try on a barrister’s robe and wig, and learned about the significance of the uniform.

I met Jamil Mohammed and Constance Whippman at 33 Bedford Row Chambers. Jamil gave us a tour of the chambers, explaining the “pigeonhole” system used for paper briefs, similar to a court dropbox or mailroom. Jamil also explained the “cab rank” rule that barristers follow, which requires barristers to take on all cases they are given unless you lack competency. I had the chance to try on a barrister’s robe and wig, and learned about the significance of the uniform.

Old Square Chambers

For two weeks of my scholarship exchange in London, I completed a mini-pupillage at Old Square Chambers. While there, I had the opportunity to observe a multiple day commercial law hearing; a medical negligence case meeting between a barrister, solicitor, expert witness, and client; an employment tribunal run by a KC; a personal injury hearing outside of London; and even a Court of Appeal case held at the Royal Courts of Justice. It was during my mini-pupillage that I came to understand that barristers refer to opposing counsel as their “learned friend” in court. How cool!

3PB Chambers

I also had the wonderful opportunity to meet several members of 3PB chambers in their London and Oxford sets. I enjoyed lunch at the Bench Table at Inner Temple with Richard Honey KC. I also had the opportunity to tour the Oxford 3PB Chambers office and meet with several members of their chambers.

Becoming a Barrister

Unlike the U.S. system where all individuals become licensed attorneys, the U.K. and many of the Commonwealth countries employ a split profession: one can become either a barrister or a solicitor. Each has a distinct training path and range of practice, with barristers occupying the traditional courtroom advocacy space.

To become a registered barrister, you typically complete an undergraduate degree in law, attend a number of qualifying sessions at an Inn of Court (10 in total, 2 must be formal dining sessions), and then you are called to the bar. After one has been called to the bar, you must then apply and be selected for pupillage: a year-long apprenticeship at a barristers’ chambers. Only after successfully completing a pupillage is one considered a registered barrister.

There are many people who have been called to the bar but have not completed a pupillage. These folks are known as unregistered barristers.

Pupillage is quite difficult to obtain; only 1 in 8 will receive an offer from a chambers to complete the year-long training required to become a barrister. In comparison, there is a 2 in 5 chance to become a solicitor.

Becoming a King’s Counsel (KC)

As barristers become more senior, some apply to become recognized as silks, or King’s Counsel (KC). This is a highly sought after distinction that typically is bestowed only after 15-20 years of practice. Only 100 or so barristers are recognized as KCs each year.

Barristers in certain areas of law are less likely to become KCs because they are not in court often enough to meet the KC criterion (e.g., tax attorneys). KCs are similar to partners at a U.S. law firm, in that they are well respected and hold senior roles at their respective barristers’ chambers. Most judges will become KCs before they begin their judicial careers.

Unfortunately, only 20% of KCs are women. During my mini-pupillage at Old Square Chambers, I had the chance to shadow and chat with Rebecca Tuck, a well-known and respected KC with an employment law practice. Rebecca and I discussed how both England and Utah can improve their gender parity in the legal profession, and the sorts of work that is being done to increase women’s advancement in law.

Modern Day Knights in the U.K.—are Judges!

During a lovely dinner at Gray’s Inn, I had the privilege of sitting next to a high court judge. I was admiring the ornate medallion he and other high court judges wore around their neck, and he kindly took the time to explain its significance Known as a decoration, the object displays a knight’s sword, belt, and spurs. The high court judge went onto explain that high court judges in England are actually recognized as knights or dames of the British Empire, which I found to be absolutely mind boggling! As women are not recognized as knights but instead as dames, they wear a different decoration than the one pictured.

Female judges, recognized as Dames Commanders of the Order of the British Empire, are addressed as My Lady or Your Ladyship. Male judges, recognized as Knights Bachelor of the Order of the British Empire, are addressed as My Lord or Your Lordship. Additionally, there are several orders, including the Knightship of Garter and the Knightship of Thistle. Male judges can be recognized as a member, commander, knight commander, and knight grand cross (in ascending order).

Bar Council

While in London, we also had the chance to meet with Bar Council Vice Chair Barbara Mills KC, Director of Policy Phil Robertson, and Head of International Policy Natalie Darby. During our meeting, we learned that Bar Council is the voice of the legal profession in the U.K., with 18,000 members who are mostly self-employed at barristers chambers. The Bar Council has a similar ability to influence legislation as the U.S. Federal Bar Association and American Bar Association.

Bar Council has conducted extensive studies related to gender parity in the legal profession. As part of its push to create greater mobility in the profession for women, people of color, and individuals from disadvantaged economic backgrounds, Bar Council has developed a formal judicial pathway program, known as PAGE. Bar Council has also established women’s forums in six circuits across England and Wales.

Law Society

We had the chance to attend a meeting with Bar Council. While there, we discussed the role of solicitor-advocates and learned more intriguing information about the split legal profession. For example, there are 200,000 solicitors in the U.K, but only 18,000 barristers. Additionally, there are about 80,000 “non-practicing barristers” or those who have passed law school and been called to the bar, but have not be granted pupillage.

We had a robust discussion about gender, ethnic/racial, and class parity in the legal profession. There are roughly 53% female solicitors, but only 35% female partners.

Pro Bono Centre

During our time in London we visited the national Pro Bono Centre and learned about the various access to justice initiatives at the centre. We learned that while pro bono is not compulsory in the U.K., it is still a huge priority for the legal profession.

Solicitor Firm Visit

We also had the chance to visit Linklaters, a solicitor firm in London. While there, we learned about what solicitor practice is like and how it differs from the role of barristers in the U.K. legal system.

Oxford and Cambridge

While in London, I took advantage of my proximity to Oxford and Cambridge and visited both of these exceptional institutions. I also had the chance to meet with several professors of medical and international law to discuss issues related to my ongoing bioethics research in the U.S. I am grateful for Old Square Chambers supporting these visits and providing me with such an excellent mini-pupillage.

Adventures Outside London

During my stay in London, I made sure to take advantage of the incredible art and history around me. I was part of the immersive Guys and Dolls production at the Bridge Theatre, front row in the yard during a rainy, avant-garde rendering of The Taming of the Shrew at the Shakespeare Globe, and in a balconette to watch The Book of Mormon at the Prince of Wales Theatre. I was honored to attend a breathtaking performance of Il turco in Italia by Rossini at the Glyndebourne Opera house as a guest of Christa Richmond, the Director of Education at Middle Temple. I visited the British Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, the National Gallery (and visiting Van Gogh exhibit), and the Victoria & Albert Museum. I made time to visit Rochester Castle (see photo), Upnor Castle, Eltham Palace, Dover’s Western Heights Military area, and the Grand Shaft Staircase. I also visited multiple London climbing gyms, including Vauxhall West, Vauxhall East, and Euston.

During my stay in London, I made sure to take advantage of the incredible art and history around me. I was part of the immersive Guys and Dolls production at the Bridge Theatre, front row in the yard during a rainy, avant-garde rendering of The Taming of the Shrew at the Shakespeare Globe, and in a balconette to watch The Book of Mormon at the Prince of Wales Theatre. I was honored to attend a breathtaking performance of Il turco in Italia by Rossini at the Glyndebourne Opera house as a guest of Christa Richmond, the Director of Education at Middle Temple. I visited the British Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, the National Gallery (and visiting Van Gogh exhibit), and the Victoria & Albert Museum. I made time to visit Rochester Castle (see photo), Upnor Castle, Eltham Palace, Dover’s Western Heights Military area, and the Grand Shaft Staircase. I also visited multiple London climbing gyms, including Vauxhall West, Vauxhall East, and Euston.

After four amazing weeks in London, we bid our Temple Bar Scholar friends good bye and traveled to Scotland, Ireland, and Holland.

Edinburgh, Scotland

While in Edinburgh, we visited Parliament House, where the Supreme Courts of Scotland are housed. We toured the epic Parliament Hall, which was built in the years 1632-1639. We met with Lady Dorrian of the Scottish judiciary over coffee and shortbread. We also met with Michael Upton and learned about the Faculty of Advocates. The Advocates Library is a copyright library, which means it is entitled to ever book published in the U.K.

While in Edinburgh, we visited Parliament House, where the Supreme Courts of Scotland are housed. We toured the epic Parliament Hall, which was built in the years 1632-1639. We met with Lady Dorrian of the Scottish judiciary over coffee and shortbread. We also met with Michael Upton and learned about the Faculty of Advocates. The Advocates Library is a copyright library, which means it is entitled to ever book published in the U.K.

We learned that there are roughly 12,000 solicitors in Scotland, but only 450 barristers. Only 50 or so people are due qualified to practice in both London and Edinburgh!

Dublin, Ireland

In Dublin, we visited the Criminal Courts of Justice and King’s Inn. While at the CCJ, we met with Judge Power and toured the architectural marvel of a building that is the CCJ (there are separate stairwells and corridors for all parties involved in cases, as well as judges and jury members). We had time to tour the holding cells at the CCJ, as well as the victims support center. We sat in on a hearing at the CCJ and then donned a gown for a formal dinner at King’s Inn!

The Hague

During the last leg of the trip, we visited the International Criminal Court and Kosovo Specialist Chambers at the Hague. While there, we met with ICC Judge Joanna Korner and Special Prosecutor Kim West. We also attended part of a hearing at the Kosovo Specialist Chambers and one at the ICC (the latter was confidential, so the gallery could view the courtroom but not hear any of the proceedings).

Thank you

I am deeply grateful to the American Inns of Court and all of the people that made this incredible trip possible. Thank you especially to Cindy Dennis, Judge Callahan, General Dunn, and the David K. Watkiss Sutherland II Inn of Court for their support.

Meg Glasmann is working as an associate attorney at Clyde Snow & Sessions. Before her current role, Glasmann clerked for Presiding Judge Michele Christiansen Forster of the Utah Court of Appeals. Glasmann’s background combines law, entrepreneurial interests, and social science. Before earning her law degree with honors distinction from the University of Utah in 2023, she held multiple management roles at the University of Utah’s Lassonde Entrepreneur Institute. She led teams that created programming, organized events, and provided mentorship to fledgling entrepreneurs. She earned two master’s degrees in educational psychology and a magna cum laude undergraduate degree in psychology with a certificate in applied positive psychology from the University of Utah. During her undergraduate years, Glasmann competed as a Division I NCAA track and field athlete and still holds the University of Utah’s collegiate javelin record. She continues to throw javelin competitively and coaches other athletes via the University of Utah Track & Field Sports Club she founded. An active member of the David K. Watkiss-Sutherland II American Inn of Court in Salt Lake City since 2020, she participated in the American Inns of Court National Advocacy Training Program in 2023. She also serves as treasurer for the Federal Bar Association Younger Lawyers Division Board.

Meg Glasmann is working as an associate attorney at Clyde Snow & Sessions. Before her current role, Glasmann clerked for Presiding Judge Michele Christiansen Forster of the Utah Court of Appeals. Glasmann’s background combines law, entrepreneurial interests, and social science. Before earning her law degree with honors distinction from the University of Utah in 2023, she held multiple management roles at the University of Utah’s Lassonde Entrepreneur Institute. She led teams that created programming, organized events, and provided mentorship to fledgling entrepreneurs. She earned two master’s degrees in educational psychology and a magna cum laude undergraduate degree in psychology with a certificate in applied positive psychology from the University of Utah. During her undergraduate years, Glasmann competed as a Division I NCAA track and field athlete and still holds the University of Utah’s collegiate javelin record. She continues to throw javelin competitively and coaches other athletes via the University of Utah Track & Field Sports Club she founded. An active member of the David K. Watkiss-Sutherland II American Inn of Court in Salt Lake City since 2020, she participated in the American Inns of Court National Advocacy Training Program in 2023. She also serves as treasurer for the Federal Bar Association Younger Lawyers Division Board.