Patrick C. Holvey

2018 Pegasus Scholar Report

When applying to the Pegasus Scholarship, I turned to the reports of previous scholars for guidance on what the experience would entail. As a result, the following report details how I spent my time in London and my takeaways and insights from the program. My advice to those interested in the scholarship:

- Every experience is one from which you can learn something, no matter how it might first appear;

- Your relationships with the people you encounter are what make the program what it is;

- Often the best moments come from those nights you hung around a little later than you originally thought you would;

- Don’t be afraid to seek out what you’re interested in—thanks to the work of scholars before you, people are interested in talking and helping you experience the program to the fullest; and

- Those six weeks go by far too fast.

The core of the scholarship is a set of placements in barristers’ chambers, which follow a week-long introduction to Legal London, which I will discuss later. During the program, I was placed in Temple Garden Chambers (one week), Ely (pronounced EEL-ee) Place Chambers (one week), and Blackstone Chambers (three weeks). My time with Temple Garden Chambers focused on personal injury cases while my time with Ely Place Chambers was centered on a coronal inquest. The end of my program at Blackstone Chambers provided a number of experiences in both appellate and trial work and procedure. While neither Temple Garden nor Ely Place provided substantive exposure to my areas of interest—intellectual property and administrative law—I found all three to be equally fascinating in completely different and, at times, unexpected ways.

Placement Week 1: Temple Garden Chambers and the Role of a Barrister

The personal injury cases I observed at Temple Garden Chambers were a great way to get my bearings in an unfamiliar legal system. There are some similarities between the legal systems in the United States and the United Kingdom: both are adversarial, the barristers are advocates for their clients’ positions, and the judiciary is a neutral arbiter of the dispute between the parties. But there are also many differences. For example, on my first day at chambers, the barrister I was assigned to went to the High Court to seek permission to bring a commitment proceeding against an opposing party for contempt of court. Unlike in the United States, in the UK, it is not infrequent that parties must seek permission from a judge to even bring certain types of actions, and doing so is especially common for appeals from courts of first instance. Secondly, where witnesses (party or otherwise) make a fraudulent statement attested to by a statement of truth (the US form is swearing under penalty of perjury), the opposing party can bring commitment proceedings against that witness in a quasi-private/quasi-criminal prosecution, which may result in a prison term of up to two years.

Barristers do more than just go to court all day, although it is a primary aspect of their practices. Over the course of my week in Temple Garden Chambers, I saw two barristers working on behalf of insurance companies to “test” the evidence of policyholders who were subject to insurance claims. The insurance companies wanted to get the opinion of a neutral barrister on how the policyholders’ evidence would hold up on cross-examination. So, with the insurance company’s solicitor on the speakerphone, the barrister questioned the policyholder. At the end of the session, after the policyholder had left, the barrister then gave the insurance company a frank assessment of what they thought about the witness and their view of whether the case was worth defending or if settlement should be a top priority.

Barristers do more than just go to court all day, although it is a primary aspect of their practices. Over the course of my week in Temple Garden Chambers, I saw two barristers working on behalf of insurance companies to “test” the evidence of policyholders who were subject to insurance claims. The insurance companies wanted to get the opinion of a neutral barrister on how the policyholders’ evidence would hold up on cross-examination. So, with the insurance company’s solicitor on the speakerphone, the barrister questioned the policyholder. At the end of the session, after the policyholder had left, the barrister then gave the insurance company a frank assessment of what they thought about the witness and their view of whether the case was worth defending or if settlement should be a top priority.

This was different from the US process in several ways. First, barristers are not permitted to “coach” witnesses on how to give evidence or subject them to mock cross-examinations before trial, witness preparation measures that most US attorneys would consider necessities of trial preparation. If a witness is given a mock cross examination, the judge must be informed of that to potentially discount the witness’s evidence. Second, with rare exception (i.e., defamation), civil trials in the UK do not have juries—the case is simply submitted to the judge following the conclusion of the evidence.

So, this “testing” serves a clear purpose. The barrister uses testing to discern how credible the witness will be to an expert judge. Direct examination of witnesses is largely gone from the English system, replaced by written witness statements submitted to the Court. The direct “examinations” that I saw in civil trials took about two minutes and consisted of the barrister asking a witness about the veracity of his or her statement. Following affirmative answers, the barrister sat down—direct examination was over; the witness statement stood on its own in submission to the judge. Witnesses really only testified in court on cross-examination.

Placement Week 2: Ely Place Chambers and Going to Trial

My second placement was with Ely Place Chambers, though I didn’t set foot in the building. I spent the week in one of the London coroner’s courts which are responsible for conducting “inquests” into deaths within the city. The field of coronal law is likely to be foreign to most US attorneys, and this placement exposed me to how divergent the US and UK common law systems are. Additionally, because the inquest spanned the week, I was able to develop a deeper relationship with the barrister I was shadowing. At every lunch and break during the proceedings, we talked at length about aspects of US jurisprudence, how his practice as a barrister functioned, and his thoughts on areas of strength and weakness in the English system as an insider. This placement was one of the highlights of my scholarship.

The Office of Coroner is one of the oldest public positions in England, dating back to the 11th century. The coroner opens inquests into suspicious deaths, deaths that implicate state action (such as terrorism, police action-related deaths, actions by the National Health System Trusts, and others), and other specialized cases. The inquest I observed looked into the death of a man who had fallen from the top of a multistory parking lot after leaving, without permission, the mental health facility where he was committed.

The Office of Coroner is one of the oldest public positions in England, dating back to the 11th century. The coroner opens inquests into suspicious deaths, deaths that implicate state action (such as terrorism, police action-related deaths, actions by the National Health System Trusts, and others), and other specialized cases. The inquest I observed looked into the death of a man who had fallen from the top of a multistory parking lot after leaving, without permission, the mental health facility where he was committed.

The coroner is tasked with answering four questions with regard to a dead body: who is it, when did he or she die, where did they die, and how did they die? The final question, how, has two parts: what was the cause of death and what were the circumstances surrounding the death? During the proceedings, the coroner calls every witness for evidence, and, while interested parties may be represented by counsel who can ask questions of the coroner’s witnesses, it is the coroner’s show. In the inquest I observed, there were three interested parties: the decedent’s family, the National Health Service Trust that ran the mental health facility, and the Metropolitan Police. Because there was a question about the actions undertaken by the state (both with respect to the policies and actions of the facility and the response of the police), a jury was empaneled to answer the four questions for the inquest through a narrative verdict.

Once a determination is reached in a coroner’s court, the coroner may prepare a “Prevention of Future Deaths” report which they file with the Chief Coroner of England and Wales. This report reviews the facts of the inquest and makes recommendations on how the death could have been prevented and how to prevent similar deaths in the future. Interested parties who are named in these reports receive copies from the Chief Coroner (they are also posted online) and must respond to the recommendations within a set period of time.

Coronal law has its own set of procedural rules, and the differences largely center on admissibility of evidence and its form. Even so, large parts of the inquest mirrored civil trials I observed during the program in so much as direct evidence is proffered via witness statement (as discussed above) and the jury selection process is incredibly brief compared to the US process (discussed below). Also, at the end of a proceeding in the English system, the coroner or judge summarizes the evidence for the jury prior to giving their final instructions. In every proceeding I witnessed, the power of the judge in the proceeding is clearly apparent, and the respect that the bar has for the aptitude of the bench is palpable.

Placement Weeks 3-5: Blackstone Chambers and the Range of a Barrister’s Role

My final weeks of the scholarship were in Blackstone Chambers. While there, I wrote research notes for the barristers and observed court proceedings. My prior placements helped to prepare me for this work, as I now had something of a foothold on English procedure and barrister practice. I enjoyed being behind-the-scenes in a barrister’s chamber. During the three weeks, I worked with three pairs of junior barristers, each with a different developing practice. It was fascinating to see the varied work of a chambers and different approaches to developing a practice all within the same set of chambers.

My final weeks of the scholarship were in Blackstone Chambers. While there, I wrote research notes for the barristers and observed court proceedings. My prior placements helped to prepare me for this work, as I now had something of a foothold on English procedure and barrister practice. I enjoyed being behind-the-scenes in a barrister’s chamber. During the three weeks, I worked with three pairs of junior barristers, each with a different developing practice. It was fascinating to see the varied work of a chambers and different approaches to developing a practice all within the same set of chambers.

Barristers at Blackstone were engaged in all manner of cases, ranging from deceit and misrepresentation surrounding the purchase of a piece of fine art, to considering if commercial agents had the right to severance pay under EU Council Directives (and the UK implementing regulations). They were also reviewing whether the statutory scheme of birth recordation in the UK permits transgendered men who give birth following their formal recognition as legal males to be recorded as “fathers” as opposed to “mothers,” and how the Government’s enquiry into the Grenfell Tower fire (different from a coronal inquest) was meeting the UK’s obligations under the Human Rights Convention. I also observed work and proceedings on commercial issues, including an appeal from the UK Employment Tribunal regarding whether UK Uber drivers were employees or independent contractors.

Other Aspects of the UK Legal System

The split bar of the English system does take some getting used to. As attorneys and counselors-at-law in the United States, every barred attorney is able to provide legal advice to clients; perform legal work such as drafting contracts or wills; and file cases and appear in court on behalf of litigants. The Bar of England and Wales is comprised only of barristers, called to the bar by one of the four Inns of Court (Inner Temple, Middle Temple, Grey’s, and Lincoln’s). The Law Society, meanwhile, is the home of solicitors. A good way to think about the split bar, in a very general sense, is to consider solicitors to be transactional attorneys and members of a litigation team within a US firm. Solicitors do the legal work that hopefully avoids disputes but, if disputes arise, are asked by clients to bring suit. They determine the goals of litigation and are the point of contact for the client. The barrister is hired by a solicitor, not directly by the client, and the barrister’s role is dependent upon the solicitor’s needs. Barristers serve as neutral but experienced advisors to solicitors seeking an outside opinion and, where the client wishes to proceed, the advocate before the court.

The split bar of the English system does take some getting used to. As attorneys and counselors-at-law in the United States, every barred attorney is able to provide legal advice to clients; perform legal work such as drafting contracts or wills; and file cases and appear in court on behalf of litigants. The Bar of England and Wales is comprised only of barristers, called to the bar by one of the four Inns of Court (Inner Temple, Middle Temple, Grey’s, and Lincoln’s). The Law Society, meanwhile, is the home of solicitors. A good way to think about the split bar, in a very general sense, is to consider solicitors to be transactional attorneys and members of a litigation team within a US firm. Solicitors do the legal work that hopefully avoids disputes but, if disputes arise, are asked by clients to bring suit. They determine the goals of litigation and are the point of contact for the client. The barrister is hired by a solicitor, not directly by the client, and the barrister’s role is dependent upon the solicitor’s needs. Barristers serve as neutral but experienced advisors to solicitors seeking an outside opinion and, where the client wishes to proceed, the advocate before the court.

In English proceedings generally, voir dire as most American attorneys know it simply does not exist. First, the attorneys are never able to ask questions of the jury. Secondly, there are no preemptory strikes. Thirdly, the judge their limits questions to jurors to knowledge of the defendant or any witnesses to be called in the trial and scheduling issues, at most. Once those questions are asked and any issues resolved, the panel is selected. The entire process took about twenty minutes for the coronal inquest I witnessed (and about thirty minutes for a criminal trial I observed).

In English proceedings generally, voir dire as most American attorneys know it simply does not exist. First, the attorneys are never able to ask questions of the jury. Secondly, there are no preemptory strikes. Thirdly, the judge their limits questions to jurors to knowledge of the defendant or any witnesses to be called in the trial and scheduling issues, at most. Once those questions are asked and any issues resolved, the panel is selected. The entire process took about twenty minutes for the coronal inquest I witnessed (and about thirty minutes for a criminal trial I observed).

The English court system is incredibly paper based. While judicial hearings in the UK are public, the workings of the court (arguments made by the parties in submissions, materials considered by the court, etc.) are not easily accessible. At best, barristers keep a spare “skeleton” brief, which outlines the argument they will make orally to the court, on hand in case a member of the press asks for it. The CM/ECF system of the federal courts, and its public facing PACER, is something that I don’t think I’ll be complaining about too much going forward.

Another striking contrast between the English and US court system that became clear to me in week two is the lack of judicial clerks. With the exception of a few “judicial assistants” who are shared among the Supreme Court of the UK and a handful of “research assistants” at the Court of Appeal, English judgeships and coroners are a solitary role. They run their proceedings essentially unassisted by any legal staff. Every observation of the English judiciary was exceptionally impressive in terms of the judges’ clear preparation for argument/trial, mastery of the facts of the case, and interest in specific points of law. The solitary practice of English judges may perhaps be a result of their solo-practice as barristers compared to the firm practice common in the States.

The Program Outside the Chambers

To be sure, the program also goes far beyond experiential learning via placements in chambers. It also provides unparalleled engagement with some of the most powerful and noteworthy figures in the British legal system along with access to unique and generally inaccessible opportunities. For example, we were able to attend both the Opening of the Legal Year ceremony held at Westminster Abbey and the Temple Church Evensong Celebration of the Michaelmas Term, two key traditional ceremonies for British legal community.

To be sure, the program also goes far beyond experiential learning via placements in chambers. It also provides unparalleled engagement with some of the most powerful and noteworthy figures in the British legal system along with access to unique and generally inaccessible opportunities. For example, we were able to attend both the Opening of the Legal Year ceremony held at Westminster Abbey and the Temple Church Evensong Celebration of the Michaelmas Term, two key traditional ceremonies for British legal community.

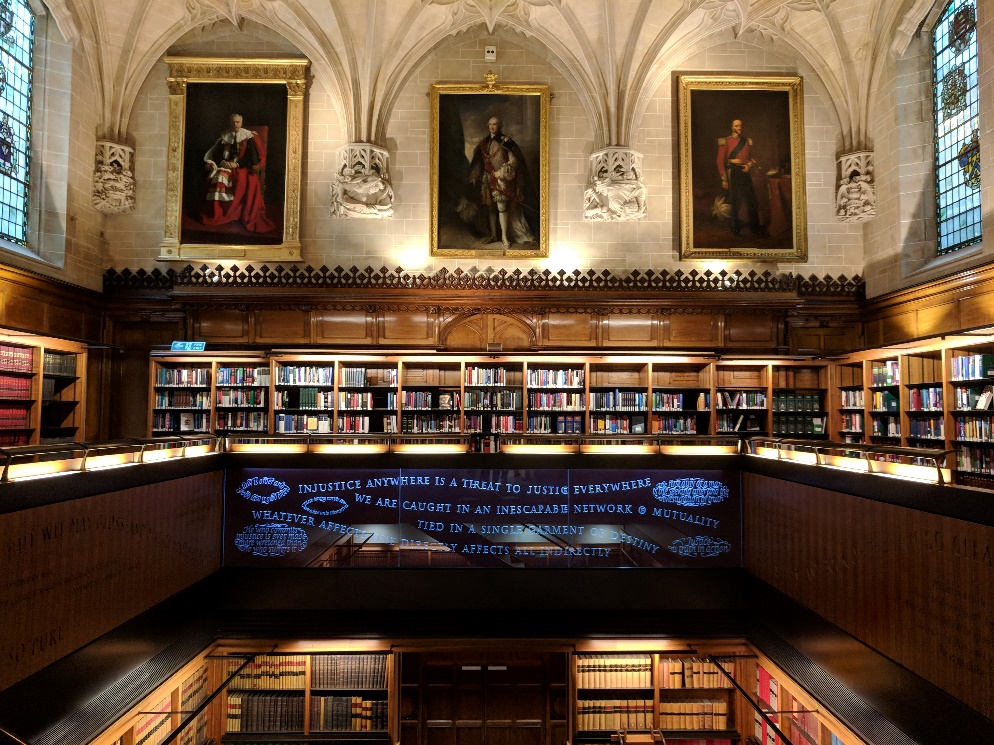

I found the time and attention given to the Pegasus Scholars by the UK legal system to be unbelievable. The program included private welcomes from both the Lord Chief Justice and the President of the Supreme Court, a question and answer session with the Master of the Rolls, and briefings on all aspects of barrister and solicitor practice from the President of the Bar Counsel and the International Director of the Law Society, among others. We also received a private tour of the Central Criminal Court (the Old Bailey) from a member of the court and observed a session of the House of Lords as a guest of Lord Woolf.

While some of these experiences were shared with the Temple Bar Scholars, a different scholarship program administered by the American Inns of Court and the Commercial Bar of the UK, my co-scholar Christie Herbert and I had four experiences unique to the Pegasus Scholarship: observing the Westminster Bridge Inquest conducted by the Chief Coroner of England and Wales, in Courtroom 1 of the Old Bailey; observing an appeal about whether financial disclosure obligations of Jersey implicated the accused’s right against self-incrimination at the Supreme Court followed by a tour of the building and tea with Lady Black (one of the Justices of the Supreme Court); and visiting Edinburgh, Scotland, and Belfast, Northern Ireland, to learn about their respective legal systems.

Christie was my steadfast companion throughout the program, and deserving of far more than this brief mention. A very important aspect of having a successful program is a willingness to really engage with the opportunities the program presents to scholars, and I was lucky to have co-scholar as engaged as Christie was. In addition to Christie, I am fortunate to now count Yvonne Wang and Charlie Piho, Pegasus Scholars from New Zealand, and Rohan Kothari, a Pegasus Scholar from India, as new friends who also provided additional views as counterpoints to the English system. Comparing, for example, the Scottish system to not only the English system but also the Indian and New Zealand systems helped to frame issues and considerations at play in common law across the globe.

Christie was my steadfast companion throughout the program, and deserving of far more than this brief mention. A very important aspect of having a successful program is a willingness to really engage with the opportunities the program presents to scholars, and I was lucky to have co-scholar as engaged as Christie was. In addition to Christie, I am fortunate to now count Yvonne Wang and Charlie Piho, Pegasus Scholars from New Zealand, and Rohan Kothari, a Pegasus Scholar from India, as new friends who also provided additional views as counterpoints to the English system. Comparing, for example, the Scottish system to not only the English system but also the Indian and New Zealand systems helped to frame issues and considerations at play in common law across the globe.

Nights and Weekends

eyond the set program, I took advantage of the opportunity to see and connect with people and places in and around London. I attended a gala dinner for my alma mater, Notre Dame, which was celebrating the 50th anniversary of its law school’s London study-abroad program. With the other scholars, I explored Greenwich, Stonehenge, Bath, Windsor Castle, and Cambridge. I had drinks with the Supreme Court’s judicial assistants (put together by the Temple Bar Scholars). And I met with Lord Kitchin, Justice of the Supreme Court, who has a specialty in intellectual property law.

Finally, Christie and I were lucky enough to observe the Bar’s commitment to mentorship and oral advocacy by attending a weekend advocacy workshop for new barristers run by Middle Temple. This was exactly the kind of unique opportunity future Scholars should be on the lookout for—it was not advertised or arranged for us; we discovered it through conversation with a barrister over lunch and made it possible by following up on our own initiative. Christie and I observed the workshop track geared towards young civil barristers. The day of exercises were led by two senior barristers, what are known as Queen’s Counsel, commonly known as QCs. With 16,400 practicing barristers at the English Bar, and only 1,600 QCs among that number, the practical experience and skill that the QCs can bring to bear in a mentorship capacity cannot be overstated.

The QCs had volunteered their entire Saturday to run the advocacy training. The participants were led through an extensive series of exercises—reviews of previously submitted skeleton arguments, mock direct examination, mock cross examination, and closing arguments. At each stage, the QCs focused intently on helping the young barristers, providing specific issues to focus on and demonstrating proper technique and form before letting the young barristers try again.

The QCs had volunteered their entire Saturday to run the advocacy training. The participants were led through an extensive series of exercises—reviews of previously submitted skeleton arguments, mock direct examination, mock cross examination, and closing arguments. At each stage, the QCs focused intently on helping the young barristers, providing specific issues to focus on and demonstrating proper technique and form before letting the young barristers try again.

It was not only incredibly educational, but I found the extent to which the QCs were dedicated to assisting the next generation of the Bar to be inspiring. One barrister told me that this level of interest in mentoring was not uncommon. It was striking to see such a deep and real commitment to the future of the profession. And it is a perfect recollection to close this report with because it draws together so much of what makes the Pegasus Scholarship so special: learning about the UK legal system from a vantage point a casual visitor would never get to experience, alongside a new friend, through an experience that Christie and I discovered and pursued on our own but which would not have been possible without the powerful support and reputation of the Pegasus Scholarship.

This is an exceptional program, one that I am very lucky to have been able to participate in. I would like to sincerely thank the Pegasus Trust, the Pegasus Scholarship Committee, and the American Inns of Court for the opportunity to engage with the legal systems of the United Kingdom as a Pegasus Scholar. The six-week program that the Pegasus Trust provides to common law lawyers from around the world is unbelievable in scope, access, and experience. I could not have imagined my time as a Pegasus Scholar would turn out to be the exceptional experience that it was.

Patrick C. Holvey is a law clerk for Chief Judge J.Rodney Gilstrap of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas. He is a member of the Giles S. Rich American Inn of Court where he serves as co-membership chair. He served on the American Inns of Court Pegasus Placement Committee from 2016–2017and is currently serving on the Program Awards Committee.

Holvey is a graduate of New York University School of Law, where he served in various editorial capacities on the Journal of Intellectual Property and Entertainment Law. After earning a bachelor of science degree in chemistry at the University of Notre Dame, where he also played the tuba in the Band of the Fighting Irish, Holvey earned a master’s degree in materials science and engineering at the Johns Hopkins University.

Before joining Gilstrap’s staff, Holvey served for two years as judicial law clerk to Judge Pauline Newman of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Washington, DC. During law school, he worked as an intern for the American Civil Liberties Union’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project and as an extern for the Criminal Division of the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of New York. He is the 2018 recipient of the Honorable Nancy F. Atlas IP American Inn of Court Sponsored Scholarship Grant for Judicial Clerks, which is administered by the IPIL Institute at the University of Houston Law Center. Following his Pegasus Scholarship, he will begin work as a trial attorney for the U.S. Department of Justice.