American Inns of Court: The Genesis

The Bencher | November/December 2023

By Ralph L. Dewsnup, Esquire1

Originally published in The Bencher, September/October 2004

Over the years it has been fascinating for me to hear different accounts of the origin of the American Inns of Court. Each person has his or her own take on who did what and how things happened. There are many versions of the story, each one bearing only partial resemblance to the others.

Over the years it has been fascinating for me to hear different accounts of the origin of the American Inns of Court. Each person has his or her own take on who did what and how things happened. There are many versions of the story, each one bearing only partial resemblance to the others.

I have heard Harold G. Christensen, the first president of the first American Inn of Court, lament that there was a general misunderstanding about the way things came together.2 He was fond of saying that the movement known as the American Inns of Court “did not spring forth fully developed, like Athena from the head of Zeus.” Rather, it evolved, over time (and is still evolving), thanks to the efforts, support, and enthusiasm of many people. Its origin is much more involved (with drama, excitement, failures, and successes) than a short article can convey.3 I can only hope to give a summary that will coincide with the memories of those who were there at various times, playing central roles in the founding of this organization, which has done so much to reclaim the law as a profession.

It is a matter of history that before he became chief justice, Warren E. Burger, then-judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit, expressed his wish that law students would receive more exposure to the practical aspects of legal practice during their law school years.4 In 1966, he encouraged and endorsed a program sponsored by the legal fraternity Phi Alpha Delta in which chapters called “Inns of Court” were established in several law schools. These chapters sought to encourage professionalism and ethics through sponsorship of a series of seminars. However, the success of the endeavor was spotty.

One person whose concerns for the lack of practical skills among trial lawyers ran parallel to those of Judge Burger was a U.S. District Court Judge in Utah named A. Sherman Christensen. Judge Christensen had urged a more practical approach to legal education in a letter to the dean of the University of Utah Law School in 1966.5

One person whose concerns for the lack of practical skills among trial lawyers ran parallel to those of Judge Burger was a U.S. District Court Judge in Utah named A. Sherman Christensen. Judge Christensen had urged a more practical approach to legal education in a letter to the dean of the University of Utah Law School in 1966.5

When it appeared that his suggestions were being underemphasized, he reiterated them to the Utah dean the next year accompanied by a copy of a speech that Judge Burger gave to the American College of Trial Lawyers in which he called for the establishment of a legal apprentice program in law schools. Still nothing significant happened. Inertial power being what it is, perhaps Judge Christensen decided to try a different approach. When he learned in 1971 that a new law school was to be established at Brigham Young University (BYU) in Provo, Utah—approximately 45 miles south of the University of Utah—he wrote to its president, Ernest L. Wilkinson, to make suggestions about not neglecting the practical aspects of legal education at the new school. He similarly pressed his views on Wilkinson’s successor, Dallin H. Oaks, and on the newly announced law school dean, Rex E. Lee.6

Lee gave Christensen the opportunity to tell the new faculty about his ideas for a curriculum that placed greater emphasis on legal advocacy. Their reception of his suggestions was tepid. After all, they had to worry about things like accreditation. Striking out into new territory was risky business for a new law school. However, perhaps in an effort to still the incessant voice of this not-so-quiet crusader, Lee invited Judge Christensen to teach a trial advocacy seminar. There, he could help at least some of the students to understand principles of courtroom advocacy that he felt were so sorely lacking among recent law school graduates.

Lee gave Christensen the opportunity to tell the new faculty about his ideas for a curriculum that placed greater emphasis on legal advocacy. Their reception of his suggestions was tepid. After all, they had to worry about things like accreditation. Striking out into new territory was risky business for a new law school. However, perhaps in an effort to still the incessant voice of this not-so-quiet crusader, Lee invited Judge Christensen to teach a trial advocacy seminar. There, he could help at least some of the students to understand principles of courtroom advocacy that he felt were so sorely lacking among recent law school graduates.

I was privileged to be one of the third-year students in Judge Christensen’s trial advocacy seminar in 1976. At the time, I was too naive to appreciate what was going on. I did not understand what a rare treat it was to have a federal judge as a law professor. What I did understand was that we were given a chance to draft real pleadings, motions, and memoranda. We discussed things such as what to wear, where to stand, how to address the court, how to make objections, how to conduct direct and cross-examination, and how to do a summation. We visited a courtroom and imagined ourselves in the crucible. He emphasized professionalism, courtesy, and legal excellence. Each student prepared a paper on some aspect of advocacy. I later learned that Judge Christensen hoped to develop a jurisprudence of advocacy. All of this was but a prelude to the founding of the American Inns of Court.

In 1977, Warren Burger, now chief justice of the United States, led a delegation of lawyers and judges on a visit to the English Inns of Court in London, England, as part of an Anglo-American exchange. Burger was so impressed with the trial skills and techniques of the advocates before the bar that he asked one of the members of the U.S. delegation, Judge J. Clifford Wallace, of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, to explore ways to promote adoption of some British training methods and means in the U.S. legal system, particularly as concerned revitalization of the Phi Alpha Delta program. Wallace circulated a “think piece” with some ideas and tried to keep the matter on the chief justice’s radar screen. He may have been a catalyst for what happened next.

In 1977, Warren Burger, now chief justice of the United States, led a delegation of lawyers and judges on a visit to the English Inns of Court in London, England, as part of an Anglo-American exchange. Burger was so impressed with the trial skills and techniques of the advocates before the bar that he asked one of the members of the U.S. delegation, Judge J. Clifford Wallace, of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, to explore ways to promote adoption of some British training methods and means in the U.S. legal system, particularly as concerned revitalization of the Phi Alpha Delta program. Wallace circulated a “think piece” with some ideas and tried to keep the matter on the chief justice’s radar screen. He may have been a catalyst for what happened next.

On the morning of August 1, 1979, BYU Law School Dean Rex Lee received a phone call from Burger asking that he and BYU President Dallin H. Oaks join him for lunch at the mountain cabin of his friend O.C. Tanner, where he was staying. Oaks and Lee made the drive to the banks of the Weber River near Provo, where they were met by the chief justice, dressed in shorts. He proceeded to don an apron and prepare lunch for them, all the while discussing his concerns over the lack of advocacy skills. The conversation included discussion of an idea that he had for the infant BYU Law School to undertake a pilot program that would combine the standards proposed by the recently concluded Devitt Committee of the U.S. Judicial Conference in combination with Phi Alpha Delta’s “Inns of Court.”7

He proposed the creation of some new “Inns of Court” for that purpose. His ideas were clearly embryonic and included a suggestion to load students onto buses to make field trips to courtrooms. I can imagine Oaks and Lee raising an eyebrow or two. However, he was the chief justice, and there was a need to improve trial advocacy. They would see what they could do.

Lee said later that as the chief justice talked about doing something to inculcate practical trial experiences, he thought of Christensen. The stars were lining up! Lee soon invited Christensen to spearhead the effort to see if Burger’s general ideas could be made a specific reality. Although Christensen was 74 at the time and professed ignorance of how either the English Inns or the Phi Alpha Delta “Inns” worked, he said yes. Lee assigned four third-year law students to assist him.8 Their research into the structure and activities of the English Inns provided fodder for lengthy discussions that took place over the next few months about how to proceed with this new project.9

They hashed and rehashed the obstacles that separated the English experience from what might be practically achievable in the United States. They conferred, as well as corresponded with Judge J. Clifford Wallace, who encouraged their undertaking. They read papers that had been published by legal scholars and discussed what they thought would work and what would not. By December, they had hammered out a draft of a plan to implement the first Inn of Court of its kind.

Their plan is much too long to restate here. However, it contains a solid skeleton for the Inn structure that exists today. It speaks of establishing an “amalgam” of the members of “the bar, the bench, and students” to improve legal advocacy. It emphasizes “proficiency, skills, and general excellence” and encourages “courtesy, consideration, and friendliness.” In language that aptly describes Christensen’s attitude toward the profession, it also states, as one of its many objectives, that the Inn is “to renew and inspire joy and zest in trial practice as a work worthy of constant effort and learning as well as of love, as inspired by the ideal of service.”10

When it came time to pick a name for this “Inn,” Lee and the students thought it should be named after Christensen. The modest Christensen insisted that it be named after Lee. The stalemate was broken when it was agreed to name it “American Inn of Court I.” As Christensen later wrote, this allowed for a II, III, IV, etc. He clearly envisioned growth of the idea.

In late December 1979, I was sitting at my desk when the receptionist said I had a call from a “Sherman Christensen.” I gulped before picking up the phone. Not many second-year lawyers get unsolicited calls from federal judges. He called me by my first name and said that he and others were about to engage in an experiment in legal education and that I was invited to participate. Was I interested? I thought it over for about a second and said yes. He said I would be receiving material in the mail in a few days. It consisted of an application for membership in an “Inn of Court” and an invitation to an organizing meeting to be held in the form of a dinner in Provo. The date selected was February 12, 1980.

At the organizing meeting I learned that the “members” who had agreed to participate in the experiment included 12 of the most outstanding senior lawyers in our state, as well as 12 junior lawyers, 12 law students, and two law professors from BYU Law School. There were also seven judges, state as well as federal (both trial and appellate). Honorary memberships were bestowed on dignitaries that included Judge Clifford Wallace, who was the evening’s featured speaker, and on the presidents and the law school deans from the University of Utah and BYU.

After the fashion of the English Inns of Court, the chief executive officer of this “American” Inn was to be its treasurer. However, due to the potential for misunderstanding if a judge were to hold such a title (with its accompanying connotations of fundraising), alternative offices were created. In the end, the American tradition of having a president as the CEO was followed, with a secretary-treasurer selected to administer finances. To ensure ongoing involvement of judges, the title of “counselor” was created. Thus, the three-member leadership of today’s Inn of Court was born. The first president was Harold G. “Hal” Christensen.11 Treasurer was M. Dayle Jeffs. Counselor was Judge A. Sherman Christensen.12

After the fashion of the English Inns of Court, the chief executive officer of this “American” Inn was to be its treasurer. However, due to the potential for misunderstanding if a judge were to hold such a title (with its accompanying connotations of fundraising), alternative offices were created. In the end, the American tradition of having a president as the CEO was followed, with a secretary-treasurer selected to administer finances. To ensure ongoing involvement of judges, the title of “counselor” was created. Thus, the three-member leadership of today’s Inn of Court was born. The first president was Harold G. “Hal” Christensen.11 Treasurer was M. Dayle Jeffs. Counselor was Judge A. Sherman Christensen.12

At the organizing meeting Judge Christensen discussed the proposed charter of the Inn and invited written comments and suggestions. I took his request to heart and naively (but gamely) submitted a long list of proposed modifications, not realizing that the charter was the work of months of thought. Not only did Christensen not take offense at my proposals, but he embraced them and invited me to participate as a member (token young lawyer?) on the Executive Committee of the Inn as programs were planned and carried out. What an experience it proved to be! Our Inn meetings were planned over sandwiches and soft drinks in Christensen’s chambers.

Over the course of the year, the presentation method that is largely in place today evolved. We tried lectures, panel discussions, and other continuing legal education (CLE)-type techniques to introduce advocacy topics. Our most successful programs occurred when practitioners would illustrate a topic (jury selection, opening statements, direct and cross examination, summation, etc.) by putting on a short demonstration (often juxtaposing “proper” with “improper” techniques) followed by lively discussion and critique by the rest of the Inn. An hour or so of presentation would be followed by refreshments and mingling.

Programs eventually became more creative and elaborate, sometimes incorporating important topics of the day or historical legal events and issues. Many Inns decided to incorporate a dinner into their regular monthly meetings. One of the chief concerns that Christensen repeated many times was that American Inns of Court had to do much more than just provide another type of CLE. Otherwise, there would be no reason for them to exist.

In the summer following the first academic year of American Inn of Court I operation, Christensen undertook a trip to England at his own expense to visit leaders of the English Inns of Court and learn from them. Whatever skepticism they may have felt at this upstart enterprise was suppressed enough that the indefatigable Christensen returned brimming with enthusiasm and new suggestions for Inn operation.

Based on his recommendations, Inn I adopted a pupillage program to better emphasize the importance of mentoring. A new classification of Inn members was also instituted. Whereas the first members of Inn I had all been called simply “members,” now the charter was amended to call the senior members (judges, lawyers, and law professors) of the Inn “Masters of the Bench” or “Benchers.” Those who had been practicing for more than three years but had not attained “Bencher” status were called “Barristers.” The students and beginning lawyers were called “Pupils.” Monthly Inn programs were organized and presented by pupillage groups formed of Benchers, Barristers, and Pupils.

Christensen felt that although there was much to be learned from the English system, it was important that any system of American Inns develop its own traditions and distinct identity. To that end, he commissioned his daughter, who was the art director of a magazine, to design an Inn insignia to capture the essence of the Inn purpose. The “logo” that is in use today contains the word “Excellentia” in an effort to express in a word what American Inns of Court should stand for. Membership certificates were printed using the American Inns of Court crest and were issued to the initial group of initiates.

Christensen felt that although there was much to be learned from the English system, it was important that any system of American Inns develop its own traditions and distinct identity. To that end, he commissioned his daughter, who was the art director of a magazine, to design an Inn insignia to capture the essence of the Inn purpose. The “logo” that is in use today contains the word “Excellentia” in an effort to express in a word what American Inns of Court should stand for. Membership certificates were printed using the American Inns of Court crest and were issued to the initial group of initiates.

By the end of 1980, Christensen saw there was enough interest in Utah to form a second Inn of Court. The name was simple enough: American Inn of Court II. This new Inn would affiliate with the University of Utah Law School. It even received some funding in the form of a small grant from the Utah State Bar. Some of the members of Inn I formed it. Then Inn I took on additional members to replace its losses. More judges became involved. A new set of students was selected.

Christensen formed an Inter-Organization Council of the American Inns of Court to foster growth of Inns and encourage adherence to the vision and concept of Inn I. I was present during the meetings with Christensen and his colleagues of the federal bench, Judge Aldon J. Anderson, Judge Bruce S. Jenkins, and Judge David K. Winder, as well as leading members of the Utah State Bar where decisions were made to move forward with this new Inn. Utah Supreme Court Chief Justice Gordon R. Hall, Professor Ronald N. Boyce, and attorneys J. Thomas Greene, Carmen Kipp, and Stephen B. Nebeker played important roles in organizing this second Inn.

Once there were two Inns, Christensen felt there was a need to create an organ for communication of matters common to them both. He knocked out a newsletter, typing it himself on a portable typewriter he owned. He made copies at his own expense and distributed them among members of the two Inns. It was complete with pithy observations and quotes that he put in a segment that he called “Inns and Outs.” He enlisted my help for the next issue or two (published intermittently) and then turned the project over to me. For a time, under the authority of the Inter-Organization Council, I was the sole copywriter, editor, occasional photographer, and publisher of the newsletter. Eventually, I engaged the services of a layout artist and the publication was improved and re-christened The Bencher, the name it bears today. The senior partner of the law firm where I worked, W. Eugene Hansen, gave his total support, financially and otherwise, to my involvement in the movement.

Christensen kept Wallace fully apprised of developments that were taking place and hoped that Wallace would continue to lend his prestige and support to the Inn project. He was sent copies of all correspondence and reports and served, in many ways, as Christensen’s liaison with Burger. They came to feel that developments were positive enough that it was time for broader publicity. Wallace, therefore, wrote an article that was published in the journal of the American Bar Association (ABA) that told of the “experiment” being conducted in Utah.13 He invited interested persons to contact Christensen.

The Wallace article caught the attention of several people. Christensen fielded inquiries from many judges and attorneys and, at his own expense, sent them information that included a sample charter and other organization papers. Federal Judge William C. Keady, from Oxford, Mississippi, was interested enough that he spearheaded the organization of American Inn of Court III in association with the University of Mississippi Law School. Albert I. Moon Jr., Esquire, from Hawaii, having had a positive experience in Christensen’s courtroom years earlier, made inquiry himself. He persuaded Federal Judge Samuel P. King to support the organization of a similar Inn in Honolulu, and American Inn of Court IV was born.

In an effort to make Inn information more available, Christensen wrote an article that was published in Federal Rules Decisions in 1982 called “The Concept and Organization of an American Inn of Court: Putting a Little More ‘English’ on American Legal Education.”14 More interest in the idea was generated, and Christensen received numerous additional inquiries. He responded to each one personally, sending copies of informational materials that he had put together.

A valuable contact that was made during this time was with Peter W. Murphy, a British barrister and member of the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple in London. Murphy was practicing law in San Francisco and was affiliated with a social organization of expatriate British lawyers called the Inns of Court Society. Murphy’s insights into the role that Inns of Court played in legal education were of great interest to Christensen. Christensen’s plans for adapting the strengths of the English Inns into the American legal system likewise intrigued Murphy. An ongoing correspondence was initiated that seemed, for a time, as if it might result in a new American Inn of Court in San Francisco. It wasn’t to be—at least, not yet.

One other inquiry, among the many that proved pivotal in the overall history of the American Inns of Court, came from a Georgetown law student named Kent A. Jordan, now a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. After completing his first year of law school, Jordan was clerking for his attorney brother in Salt Lake City, Utah, when he came across the ABA Journal article by Wallace. He was bold enough to contact Christensen to find out about this new idea and was granted an extended audience with Christensen. He left the meeting loaded down with materials to share with the administrators at Georgetown.

When Jordan returned to school, his persistence in seeking support for the program eventually put him in touch with Professor Sherman Cohn, who studied the materials, talked with Christensen by phone and, with the support of the law school dean, agreed to try to get something going at Georgetown.

When Jordan returned to school, his persistence in seeking support for the program eventually put him in touch with Professor Sherman Cohn, who studied the materials, talked with Christensen by phone and, with the support of the law school dean, agreed to try to get something going at Georgetown.

A series of fortuitous circumstances put both Cohn and Jordan in touch with Judge Howard T. Markey, chief judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. Markey had heard about the Inns of Court from both the chief justice and the chief’s administrative assistant, Dr. Mark Cannon. He was enthusiastic about the program and got on board to help organize another American Inn of Court. (This was the sixth Inn, a fifth having been formed in Brooklyn a short time before.)

A series of fortuitous circumstances put both Cohn and Jordan in touch with Judge Howard T. Markey, chief judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. Markey had heard about the Inns of Court from both the chief justice and the chief’s administrative assistant, Dr. Mark Cannon. He was enthusiastic about the program and got on board to help organize another American Inn of Court. (This was the sixth Inn, a fifth having been formed in Brooklyn a short time before.)

By this time, the volume of interest being generated across the country started to overwhelm Christensen. He was still paying all of the expenses and handling all of the correspondence himself, believing that treating the program as an expense of the court system was not officially approved. I remember vividly being called by Christensen one morning to come to his chambers on a matter of Inn of Court business. I walked the block or so to get there and found the judge in an uncharacteristically somber mood. In my naiveté I had supposed that the surge of interest in the fledgling movement was good news. He confided that he had been trying to get some indication of where the chief justice stood on developments. He expressed concern that unless something more concrete than mere expressions of encouragement was forthcoming the movement was going to sputter to an end. He told me that he had written to Burger to recommend a course of action some time ago but that he had not heard back from him. He seemed frustrated and sad. I suppose he wanted to prepare me for the disappointment that, to him, must have seemed inevitable.

It seems like it was only a few days later that I got a phone call from Christensen. His tone of voice was decidedly more upbeat than it had been at our last meeting. He said he had just heard from the chief justice, who had expressed enthusiasm for the way that things were going and said that he intended to appoint an ad hoc committee of the U.S. Judicial Conference to study and develop the American Inns of Court concept. He had asked Christensen for the names of persons that should be invited to serve on the committee. I knew nothing of how such things worked. What I gathered was that Christensen intended to nominate several of the people who had worked with him on Inns, including me. He added, however, that given the probable small size of the committee and my relative youth and inexperience at the bar, I would probably not be appointed. At that point, it didn’t matter to me. The U.S. Judicial Conference was not an entity that I knew anything about. All I knew was that the life of the American Inns of Court had been extended. That was wonderful news!

In September 1983, my newly hired secretary brought the mail into my office with special reverence. She said I had received a very important letter and was impressed that such a communiqué would come to me. When I saw the letter from the Chief Justice of the United States, I assured her that this was not a regular occurrence. The letter announced the formation of the Ad Hoc Committee and invited me to serve on it. The first meeting of the committee was set for October 26, 1983, in Washington, DC. I hastily wrote the chief justice my letter of acceptance.

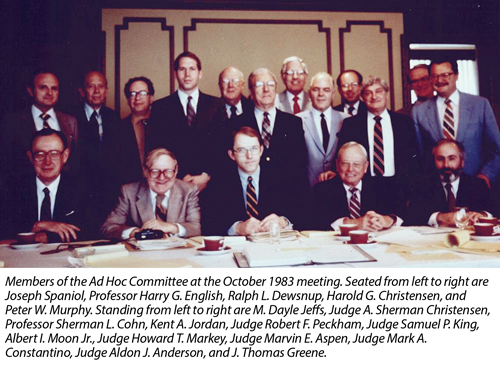

The first meeting of the Ad Hoc Committee was convened in the West Conference Room of the Supreme Court of the United States. It was the first time that most of us would know who our committee mates were to be. I don’t think I was the only one to be a bit dazzled by our surroundings. Even seasoned judges had not been in the inner sanctums of the Supreme Court building. Besides myself, those present included Christensen, who had been appointed chair of our committee, as well as Judges Aldon J. Anderson, Howard T. Markey, William C. Keady, Samuel P. King, Robert F. Peckham, Marvin E. Aspen, Bruce S. Jenkins, and Mark Costantino; Professors Sherman L. Cohn and Harry G. English; attorneys Peter W. Murphy, Albert I. Moon Jr., Harold G. Christensen, and M. Dayle Jeffs; and law student Kent A. Jordan.

In addition to committee members, Judge J. Clifford Wallace and Solicitor General Rex Lee were present, as was the chief justice’s administrative assistant, Dr. Mark Cannon. Each gave brief remarks, reminding us that this was a rare event—full of great potential. The chief justice himself spent time with the committee to offer words of encouragement, even hosting us at a luncheon in the justices’ private dining room.

Among the activities of the first meeting of the Ad Hoc Committee was the presentation of reports from committee members about the activities of each of the Inns with which they were associated. Each person had a different story to tell. Christensen’s steady hand was deftly inserted to keep us from trying to define the Inns of Court as a law school extension or a CLE program or an apprenticeship plan or even a transplantation of English methods. His vision was clear: This was something new, different, and unique in the annals of American law.

Among the activities of the first meeting of the Ad Hoc Committee was the presentation of reports from committee members about the activities of each of the Inns with which they were associated. Each person had a different story to tell. Christensen’s steady hand was deftly inserted to keep us from trying to define the Inns of Court as a law school extension or a CLE program or an apprenticeship plan or even a transplantation of English methods. His vision was clear: This was something new, different, and unique in the annals of American law.

At the end of the first day of meetings, Christensen appointed a subcommittee consisting of myself, Peter Murphy, and Judge Howard Markey to draft a statement of objectives for the committee. We were to have the objectives written by the next day. As daunting as the task seemed to me, Markey seemed to have a vision of what should happen. He told Peter and me to meet him in the morning so we could discharge our duty. And, thanks to the judge, discharge it we did.

The next morning, I acted as scribe while Markey, in effect, dictated a rather complete statement that, with a few suggestions from Peter, and even fewer from me, was presented to the whole committee by nine o’clock. After review and discussion, our draft statement was unanimously adopted in the form of a 13-paragraph resolution. That became our charter to guide the work of the committee over the next two years.

Shortly after the first meeting, Judge Susan H. Black from the Middle District of Florida (now a senior judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit) was invited to join the Ad Hoc Committee. Then, following a committee meeting in San Diego, California, in February of the next year, Judge William B. Enright of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California, who had organized an Inn there and had applied for a charter, was likewise asked to lend his considerable leadership abilities and enthusiasm for the movement by becoming a member of the committee. Both were instrumental in the establishment of Inns and in the development of the fledgling movement.

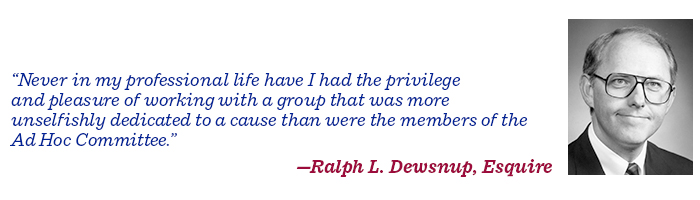

Never in my professional life have I had the privilege and pleasure of working with a group that was more unselfishly dedicated to a cause than were the members of the Ad Hoc Committee. Personal agendas, if they ever existed, were laid aside. Work assignments were completed on time. Disagreements were resolved. Personality differences were overlooked. We moved forward, as one body, to answer numerous questions: How big should an Inn be? What should be the criteria for Inn membership? What categories of membership should there be? How many persons in each membership category should be in a single Inn? How many Inns should there be? How should an Inn be started? Should there be a national umbrella organization? If so, what form should it have? What should be the relationship of local Inns to a national structure? How should individual Inns be financed? How should a national organization be financed? What should be the respective roles of judges, experienced lawyers, less experienced lawyers, law professors, and law students within an Inn? How often should local Inn meetings be held? What should be accomplished in local Inn meetings? How often should national meetings be held? What should national meetings consist of? What kind of leeway could or should be given to a local Inn to deviate from national guidelines? How should national guidelines be promulgated? What should be the leadership structure of a national organization? How should national leaders be selected? And so forth.

For the first eight months of operation of the Ad Hoc Committee, Christensen set the agenda and presided over its meetings. But on July 21, 1984, at the age of 79, he announced his retirement from the post and the appointment of his longtime colleague, Judge Aldon J. Anderson, of the U.S. District Court for the District of Utah, to succeed him. It is no criticism of Anderson to tell of the general sadness that attended the announcement of Christensen’s departure. He had, almost single-handedly, served as the chief architect and builder of the American Inns of Court during the infancy of the organization. He was not only respected by committee members but had become beloved. His personal sacrifices and dedication had carved a stone out of the mountain that had begun to roll forth. Committee members were committed to finish the job that he started.

For the first eight months of operation of the Ad Hoc Committee, Christensen set the agenda and presided over its meetings. But on July 21, 1984, at the age of 79, he announced his retirement from the post and the appointment of his longtime colleague, Judge Aldon J. Anderson, of the U.S. District Court for the District of Utah, to succeed him. It is no criticism of Anderson to tell of the general sadness that attended the announcement of Christensen’s departure. He had, almost single-handedly, served as the chief architect and builder of the American Inns of Court during the infancy of the organization. He was not only respected by committee members but had become beloved. His personal sacrifices and dedication had carved a stone out of the mountain that had begun to roll forth. Committee members were committed to finish the job that he started.

Within the next year, Anderson guided the committee to complete its work, and a report was submitted to the Judicial Conference in 1985 that ultimately resulted in the creation of the American Inns of Court Foundation as a nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation. Signing the incorporation papers were Burger, Lee, and Christensen, three people without whose vision, support, enthusiasm, and hard work, the American Inns of Court would never have come into being. All of them have since passed on, but I can safely say that, notwithstanding the talent, experience, vision, and enthusiasm of these extraordinary individuals, none of them ever imagined that the American Inns of Court would become what they are today. For that part of the story, we are indebted to others whose stories are told elsewhere in this issue. My only hope is that we do not drop the torch that has been passed to us, but that we hold it high—very high indeed.

Ralph L. Dewsnup, Esquire, is the former president and a founding member of Dewsnup King Olsen Worel Havas in Salt Lake City, Utah. He is an Emeritus member of the Aldon J. Anderson American Inn of Court and served on the American Inns of Court Board of Trustees from 1988 to 1998. Dewsnup was the 1992 recipient of the American Inns of Court A. Sherman Christensen Award.

Ralph L. Dewsnup, an attorney practicing in Salt Lake City, Utah, was a charter member of American Inn of Court I in 1980 and a member of its first Executive Committee. He served as editor of The Bencher and its predecessor publication, 1982–1990; as a member of the U.S. Judicial Conference Ad Hoc Committee on American Inns of Court, 1983–1985; as secretary to the Board of Trustees of the American Inns of Court Foundation, 1985–1996; as treasurer of the American Inns of Court Foundation, 1996–1998; as trustee of the American Inns of Court Foundation, 1988–1998; and as president of the Aldon J. Anderson American Inn of Court (VII), 1991–1992. He received the Foundation’s A. Sherman Christensen Award in the Supreme Court of the United States in 1992. He is now an emeritus trustee of the American Inns of Court Foundation and an active member of the Aldon J. Anderson American Inn of Court (VII) in Salt Lake City.

Harold G. Christensen died in 2012. At the time this article was originally written he was an attorney in Salt Lake City. He was a charter member and president of American Inn of Court I beginning in 1980; was a member of the U.S. Judicial Conference Ad Hoc Committee on American Inns of Court, 1983–1985; and was a charter trustee on the first Board of Trustees of the American Inns of Court Foundation. He was an emeritus trustee of the American Inns of Court Foundation and an emeritus member of the A. Sherman Christensen American Inn of Court (I). He served as assistant attorney general of the United States in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations.

Most of the history of which I write is something that I experienced firsthand or heard from the lips of those who lived it. Many other people were participants in the early history of the American Inns of Court movement who may have different perspectives and recollections than my own. I still have boxes of documents that chronicle the early history of the American Inns of Court movement. Additional accounts of the events that I describe may be found in Paul E. Pixton, The American Inns of Court: Reclaiming a Noble Profession (1997) (published by Matthew Bender); A. Sherman Christensen, “The Concept and Organization of an American Inn of Court: Putting a Little More ‘English’ on American Legal Education,” 93 F.R.D. 807 (1982); Transcript of interview with A. Sherman Christensen conducted by the AICF Strategic Planning Committee at Brigham Young University on August 20, 1994, copy in the possession of the author; A. Sherman Christensen, Persons and Processes, An Anecdotal View of Federal Judicial Administration, 1954 to 1991 (1993), (unpublished manuscript in the possession of the author).

See speech given to the American College of Trial Lawyers on April 11, 1967, published in Warren E. Burger, Delivery of Justice: Proposals for Changes to Improve the Administration of Justice, (College of William and Mary Press and West Publishing Co., St Paul, Minn. 1990) 157.

Letter to Dean Samuel D. Thurman dated May 31, 1966, as quoted in A. Sherman Christensen, Persons and Processes, supra note 3, at 240. Judge Christensen had seen the low level of practical understanding that law school graduates had of court room decorum, procedure, and principles of advocacy.

Before his appointment as BYU president in 1971, Oaks had served as acting dean of the University of Chicago Law School and as executive director of the American Bar Foundation. After he left the presidency of BYU he served as an associate justice of the Utah Supreme Court from 1980 to 1984. Rex E. Lee later became head of the Civil Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, then solicitor general of the United States. He became president of Brigham Young University in 1989.

The Judicial Conference of the United States’ Committee to Consider Standards for Admission to Practice in the Federal Courts was chaired by Judge Edward Devitt and became known as the Devitt Committee. It issued recommendations in 1978 and 1979 that generated national attention.

Assigned to assist Christensen were William H. Orton (later elected to Congress from the State of Utah), Vaughn Crawford, Denver C. Snuffer, and Michael S. Eldredge.

Christensen, Principles and Processes, supra note 3, at 245.

Pixton, supra note 3, at 71-72.

Hal Christensen’s original title was “Master of the Bench.” The members of the Executive Committee of the Inn were called “Benchers.” Finally, it was decided that senior experienced members of the Inn would be called Masters of the Bench or “Benchers.”

The Executive Committee of the Inn included federal judge Aldon J. Anderson, state judges J. Robert Bullock and Christine M. Durham, law professor James E. Sabine, attorney Ralph L. Dewsnup, and law student William H. Orton.

J. Clifford Wallace, “American Inns of Court: A Way to Improve Advocacy,” 68 A.B.A.J. 282 (March 1982).

93 F.R.D. 801 (1982).